1. The cup is on the table. Located Reference Object Object

Figure Ground |

|

Space

The expression of spatial location would appear to be one of the most fundamental semantic notions common to all humans. After all, we seem to have a good idea of where we are most of the time. Spatial language turns out to be anything but a simple reflection of an objective reality. Recent cross-linguistic research has revealed a surprising degree of variation exists in spatial expressions between languages.

Languages locate objects in relation to some reference point. Herskovits (1986) refers to the located entity as the located object. She calls the noun phrase that specifies the location the reference object. Talmy (1983) refers to these notions as figure and ground, respectively. Spatial locations are essentially relations between the located object and a reference object:

1. The cup is on the table. Located Reference Object Object

Figure Ground |

|

Talmy ([1983] 2000: 184) figure and ground as:

“The Figure is a moving or conceptually movable entity whose site, path, or orientation is conceived as a variable the particular value of which is the relevant issue.”

“The Ground is a reference entity, one that has a stationary setting relative to a reference frame, which respect to which the Figure’s site, path, or orientation is characterized.”

Talmy introduces the notion of relevance into his definition of figure since the speaker’s perspective determines what is picked out at the figure. In many cases, either object in a spatial relation can be picked out as the figure:

2a. The lamp is over the table. b. The table is under the lamp. |

|

A similar relation holds for deictic statements. The deictic phrase in (3) points to a located object relative to a reference object – the speaker. Deixis as well as spatial location have the same relational foundation.

3. That cat

Talmy (2000: Vol. I p. 183) hypotheses the following features determine which objects speakers select as the figure and ground:

Figure |

Ground |

has unknown spatial (…) properties to be determined |

acts as a reference entity, having known properties that can characterize the [figure’s] unknowns |

more movable |

more permanently located |

smaller |

larger |

geometrically simpler (often point like) in its treatment |

geometrically more complex in its treatment |

more recently on the scene/in awareness |

earlier on the scene/in memory |

of greater concern/relevance |

of lesser concern/relevance |

more salient, once perceived |

more backgrounded, once [figure] is perceived |

more dependent |

more independent |

7.1 The Geometry of Linguistic Space

We learn to think about space in school as a three-dimensional Euclidean projection. In Euclidean space, parallel lines never meet. We may also know about Riemannian geometries in which parallel lines meet or grow farther apart, but these geometries do not seem to apply to the everyday world.

Although spatial concepts appear to be stable and universal, a closer look at the language we use to express spatial relations reveals the degree to which speakers impose spatial relations on the perceived world. Consider the following sentence:

4. The lamp is in the corner of the room.

Hearing this sentence, we would not expect the lamp to be plastered into the corner. Instead we use our knowledge of lamps to construct a scene in which the lamp may be standing in the vicinity of the corner.

In the sentence:

5. I have a pen in my hand.

the pen is only partly inside the contour of the hand. The sentence does not specify whether the hand is open or closed, but we assume the pen is in contact with the palm rather than resting on the opposite side of the hand.

To the degree we use our knowledge of the properties of located objects and reference objects, we linguistically warp space to express spatial relations.

7.2 Topological Locations

Topological locations are invariant with respect to changes in the reference object. The three basic topological locations are proximity, containment, and exteriority. They are topological because they remain the same no matter what angle the located object is viewed from.

Proximity refers to the near or total spatial overlap of the located object and the reference object. Consider the following expressions of proximity:

6a. The fly is on the wall.

b. Harry is at the fence.

No matter how the fly or Harry is viewed, their relation of proximity to the reference object remains the same. The fly in (5a) is actually in contact with the wall, while Harry need only be standing near the fence in (5b). The distance between the located and reference objects in expressions of proximity depends on the properties of the objects. Speakers use their knowledge of the located objects and reference objects to calculate the distance needed to express proximity. The expression of proximity uses a conceptually constructed space.

In addition to proximity, the English preposition at asserts a bounded feature for the objects being located:

7a. ?? Water is at the fence.

b. ?? Harry is at water.

With the expression of a bound through definiteness, the sentences become acceptable:

8a. The water is at the fence.

b. Harry is at the water.

In these sentences, the water has a boundary or edge.

The preposition on requires contact between the located and reference objects in addition to the other properties. The contact does not have to be direct – merely supportive in an extended sense. In the sentence:

9. The apple is on the table.

The apple does not have to be in contact with the table. It could be resting on a table cloth or stack of books. The nature of the contact expressed by on depends on the dimensionality of the reference object, as seen in the following examples:

10a. The clothes are on the clothesline.

b. The picture is on the wall.

One-dimensional objects such as clotheslines or fishing lines can provide support from above, while two-dimensional objects such as walls or paper can provide support from the side. For one-, two- and three-dimensional objects, on is associated with contact between the located object and the surface of the reference object.

7.2.2 Containment

Containment denotes the inclusion of a located object in the reference object. Containment may be: i. either partial or total, ii. apply in any dimension, and iii. be either real or virtual:

11a. The books are in the box.

b. There’s a crease in the bedspread.

c. What do you have in mind?

The books may be completely or only partially contained by the box. The box may also be opened on its top, or on its side. What matters is whether the books are in contact with the box’s interior in some fashion. The dimensional properties of the reference object are shown in (11b). Two-dimensional objects such as paper and blankets have interiors within their boundaries. Their interiors are simultaneously potential supports. The located object must be part of the two-dimensional reference object for containment to supercede support (Herskovits 1986):

12a. ?? The check mark is in the page.

b. The check mark is in the margin.

What counts as an inherent part of a located object is not obvious:

13a. There is a blemish on your skin.

b. I found a scratch on my car.

The mind in (11c) is treated as a metaphorical container with the potential to contain ideas and more. The goddess Athena supposedly sprang from the mind of Zeus.

7.2.3 Exteriority

Exteriority refers to the relation in which the located object is external or outside of the reference object. Exteriority is a topological relation because the viewer’s perspective does not affect the relation. Exteriority applies regardless of whether the located object is completely or partially outside the reference object:

14a. The ball is out of the box.

b. Bill is outside the room.

The dimensionality of the reference object also affects the application of exteriority. The reference object must have an interior for the located object to be exterior to:

15a. ?? The clothes are outside the clothesline.

b. ?? Jane stepped out of the spot.

Although away also appears to mark exteriority, this effect is entailed by its use to indicate non-proximity. Consider the sentence:

16. Mark is away from his home.

If Mark is not close to home then he must be somewhere outside the home. Away can be analyzed as the negation of proximity.

7.3 Cross-linguistic Encoding of Topological Relations

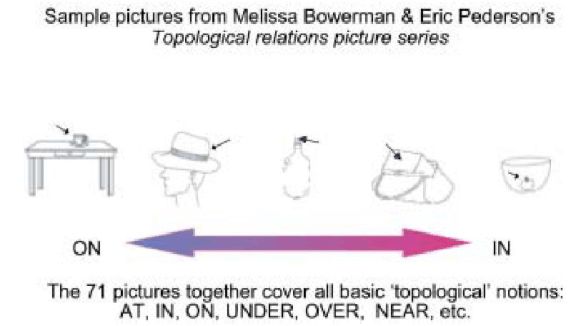

Melissa Bowerman pioneered the cross-linguistic study of topological encoding. She initially looked at the encoding of in and on in English, Dutch, Spanish and Berber.

In a recent article (Language 79:485-516), Steve Levinson and his coworkers examine the topological relations of proximity and containment in a sample of nine languages.

LANGUAGE AFFILIATION LOCATION DEMOGRAPHY CONSULTANTS RESEARCHER

Basque Isolate Europe 660,000 26 I. Ibarretxe

Dutch Indo-European Europe 20,000,000 10 D. Wilkins,C. de Witte

Ewe Niger-Congo West Africa 3,000,000 5 F. Ameka

Lao Tai-Kadai Southeast Asia 3,000,000 3 N. Enfield

Lavukaleve Isolate Solomon Islands 1,150 1 A. Terrill

Tiriyó Cariban South America 2,000 10 S. Meira

Trumai Isolate South America 50 3 R. Guirardello

Yélý̂ Dnye Isolate Papua New Guinea 3,750 4 S. Levinson

Yukatek Mayan Mesoamerica 700,000 5 J. Bohnemeyer, C. Stolz

They used Bowerman’s set of pictures to elicit spatial relations from speakers of these languages. Each picture contains a line drawing with the located object shown in yellow. The speakers were asked questions of the form Where is the [located object]? An example of their stimuli is shown below.

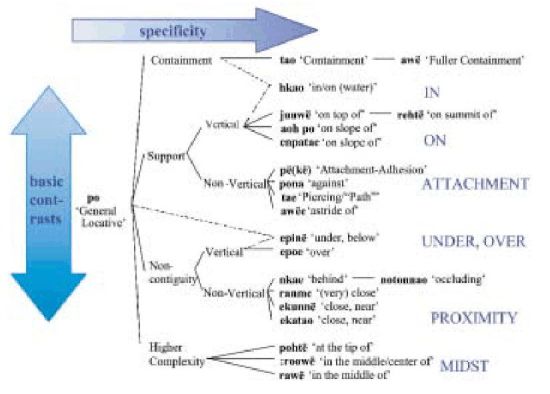

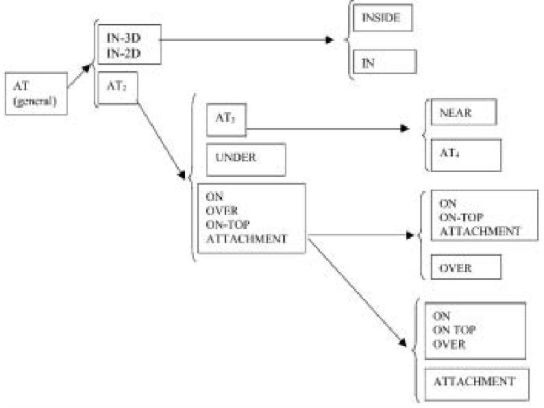

They report that the languages show considerable diversity in the range of lexical devices for encoding spatial relations. English relies primarily on prepositions, but some languages (e.g., Basque, Trumai) use relational nouns instead. English uses the relational nouns side and top in combination with prepositions to express spatial relations, e.g., inside, outside, on top. Still other languages (e.g., Dutch, Ewe, Yélî Dnye) use positional verbs similar to the English verbs sit, stand, lie, etc. The number of spatial adpositions found in the language sample varied between 2 for Yukatek and Lao, 50+ for Dutch and Yélî Dnye, and 100+ for Tiriyó. The languages with large numbers of spatial adpositions organized them into hierarchical relations. Levinson et al. provide the following ‘map’ for the adpositions in Tiriyó.

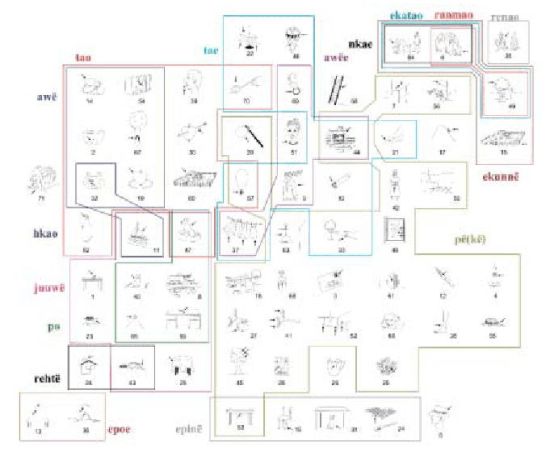

Levinson et al. tested the hypothesis that all languages apply their basic adpositions for in, on, under and near to the same core set of topological relations. This hypothesis is derived from the idea that spatial relations are universal since they directly encode basic elements of neurocognition (Pinker 1994). Levinson and coworkers tested the hypothesis by laying out their stimuli in a two-dimensional grid and tracking the extensional set for the adpositions in each language. The result of applying this process to Tiriyó is shown below.

Tiriyó uses sixteen different adpositions to describe the scenes in this grid. The adposition hkao ‘(be) in water’ used for scenes 11 and 32 is distinctly un-English. The adposition pë(kë) has the widest coverage, such as a jewel on a necklace (57), a spider on a ceiling (7), and a stamp on an envelope (3). It is not used for a shoe on a foot (21), a ring on a finger (10), or a tree on a mountain (17). The authors give this adposition the approximate gloss of ‘attached to.’ It contrasts with the adposition awëe, which they gloss as ‘astraddle’. Tiriyó speakers use awëe

for earrings (69), necklaces (51) and clothes on a clothesline (37) – relations that an English speaker also feels involve attachment.

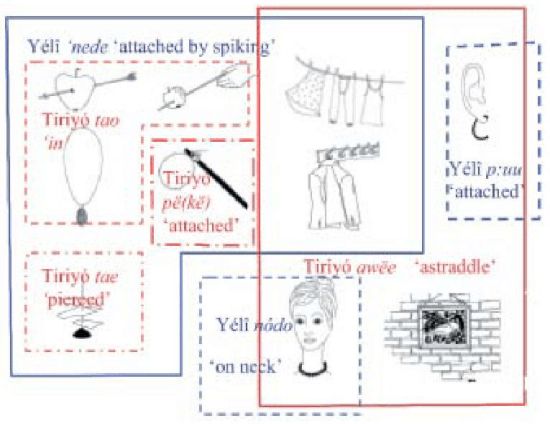

The following picture shows some of the contrasts between Tiriyó and Yélî Dnye for the adpositions in the attachment/suspension area. This area is not marked explicitly in English, but seems to feature prominently in other languages. The Tiriyó and Yélî Dnye data suggest that this area exhibits tremendous variation between languages.

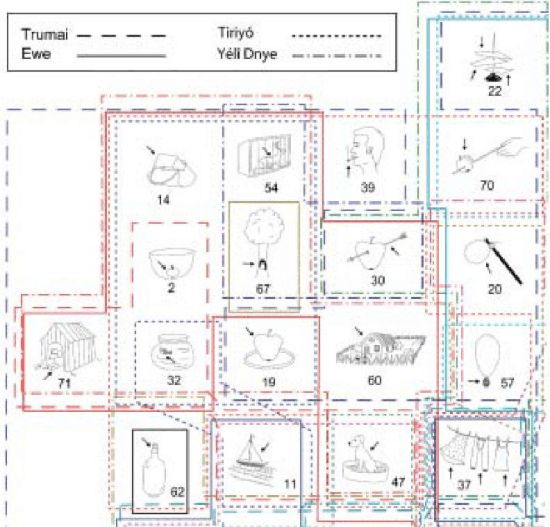

A more dramatic display of these cross-linguistic differences in semantic extension is shown by the authors’ comparison of four languages across the complete grid. I can only show the section of the grid for containment, but this is enough to demonstrate the numerous differences in the way languages divide semantic space. The authors conclude that there is no evidence for the prototype categories in, on or near.

The authors propose a ‘successive fractionation’ for spatial relations which is the result of ‘universals and tendencies in human organization of the environment.’ They find evidence for an IN-CONTAINER focus that encodes the result of storing things in containers for different purposes. Hunter-gatherer cultures like the Australian Aborigines made little use of containers, using flattish trays instead. The Australian languages show a corresponding lack of fractionation of the IN field, and instead use a single nominal to express IN/UNDER concepts. In the same way, the ON field becomes more differentiated in cultures that use elevated working surfaces and storage off the ground level. The Tiriyó hkao adposition for things located in water is a further demonstration of the importance of the aquatic environment to Cariban cultures. The authors’ diagram of successive fractionation is shown below.

Spatial Relations in Five Mayan Languages

7.5 Functional Relations

I. Nyoman Aryawibawa (2008) explored the semantics of spatial relations in Rongga, Balinese, and Indonesian. These languages employ unmarked prepositions to express normal relations between objects and marked prepositions to express abnormal relations.

|

|

|

|

Rongga

|

Kain meja one meja |

Li’e munde one mok |

|

cloth table on table |

that orange in bowl |

|

‘The table cloth is on the table’ |

‘The orange is in the bowl’ |

Changing to an abnormal relation between the figure and ground results in the use of a marked preposition. The marked form is used if the table cloth is folded and then put back on the table or if a ribbon is put in the bowl instead of an orange.

|

Kain meja zheta wewo meja |

Pita zhale one mok |

|

cloth table on table |

ribbon in bowl |

|

‘The table cloth is on the table’ |

‘The ribbon is in the bowl’ |

Aryawibawa contrasts Levinson et al’s topological categories with those of Rongga, Balinese, and Indonesian:

|

|

|

|

|

Levinson et al: |

attachment |

superadjacency |

full containment |

subadjacency |

|

|

|

||

Aryawibawa: |

function |

location |

||

7.6 Projective Locations

Projective locations depend upon the viewer’s perspective or properties of the reference object. A ball could be in front of a desk from one perspective, beside the desk from another, and behind the desk from a third perspective.

|

|

Some objects have conventional features that speakers treat as fronts or backs. The back of a chair provides back support. The front of a house is marked by the main entry way. Objects may be located in relation to the fronts, backs or sides of reference objects. Speakers must decide whether to use their own perspective or the features of reference objects to encode projective locations.

7.6.1 Front

The ‘front’ of an object depends on properties of the reference object and/or the perspective of the viewer. Languages chose different vantage points to determine a viewer’s perspective. English uses the side of the reference object facing the viewer as the ‘front’. Hausa uses the opposite side of the reference object, the side facing away from the viewer as the ‘front’ (Hill 1974, 1982). In the situation shown below, an English speaker would say the spoon is in front of the pumpkin. A Hausa speaker would say (Hill 1982:21):

16. Ga cokali can baya da k’warya.

look spoon there back with pumpkin

‘There’s the spoon behind the pumpkin’

There is more variation between languages in the attribution of ‘front’ and ‘back’ to inanimate objects. The front of vehicles is the part facing the forward motion. Even though ships have bows rather than fronts, we can still locate an object in front of a ship. The fronts of chairs and houses are determined by the convention point of access. This convention applies to appliances such as tvs and radios whose access point – the ‘on’ button, defines the front.

Other languages impose an anthropomorphic image on inanimate objects to a much greater extent. Languages that make use of relational nouns rather than adpositions are especially prone to attribute fronts to things. The Mayan language K’iche’ uses a single preposition in combination with a set of relational nouns to express spatial location (Kaufman 1990:77):

|

Prep. |

Rel. Noun |

English Equivalent |

|

chi + ‘at, on’ |

xee’ ‘root’ chii’ ‘mouth’ wi’ ‘head’, ‘hair’ iij ‘back’ wach ‘face’ |

‘below’, ‘beneath’ ‘next to’ ‘above’, ‘on top of’ ‘behind’, ‘outside’ ‘in front of’ |

K’iche’ and English speakers agree on the features for many objects. Both would define the ‘front’ (English)/‘face’ (K’iche’) by reference to the front door (u:-chii’ jah ‘its-mouth house’ in K’iche’). Both would agree on a located object being ‘beneath’(English)/‘root’ (K’iche’) a chair or table. But, K’iche’ speakers extend their relational nouns in ways that English speakers cannot predict. Rather than saying something is ‘on’ the ground, K’iche’ speakers say it is on the face of the ground (chi+u:-wach uleu). Rather than saying something is on top of a house, K’iche’ speakers say it is on the back of the house (chi+r-iij lee jah).

Other projected locations include back/behind, below, above, and left/right.

7.5 Absolutive Systems

Levinson (1996) describes two other types of frames of reference: intrinsic and absolutive.

Language like English use a relative system of spatial reckoning for projected locations. A relative system is based on the speaker’s or hearer’s perspective or the features of the reference object. These projections may be either relative or intrinsic.

Levinson (1996) provides evidence that speakers of other languages employ an absolutive system of spatial reckoning. An absolutive system is based on a fixed set of spatial coordinates, eg., north, south.

Tzeltal Mayan has an Absolutive system of spatial reckoning based on the predominant uphill/downhill lay of the land (along a South (uphill)-North (downhill) axis):

|

|

Verb |

Position |

Relation |

|

UP DOWN |

mo ‘ascend’ ko ‘descend’ |

kaj ‘be above’ pek’ ‘be low down’ |

ajk’ol ‘uphill’ alan ‘downhill’ |

e.g., ‘The rain is descending’ (i.e., coming from the south)

‘It (a puzzle piece) goes in downhillwards’

Tzeltal children begin to use the Absolute vocabulary in the one- and two-word stage to refer to vertical relations (with verbs of falling and climbing) as well as horizontal relations (movement between houses or of toy cars on the flat patio) (Brown 2001).

The core semantics for the children’s verbs mo/ko are restricted at first to local places (particular houses in the local compound). The children generalize these verbs to novel contexts such as moving objects into trees, onto beds, up onto the roof, and to and from particular houses.

Marquesan, a language of French Polynesia, has speakers that live almost exclusively on islands. As a seafaring people, the Marquesan speakers use the directionals “Seaward,” “inland,” and “Across” (or to:place name). The interesting distinction between this spatial reference system and that of Tzeltal is the while in Tzeltal “Uphill” will always denote one direction, “seaward,” though still an absolute spatial reference (as the sea isn’t going anywhere), can mean a different direction based on where you are on the island. The semantic implications of this are fascinating, in that a speaker must constantly know exactly where they are with respect to the ocean in order to have any frame of reference for where anything else is. Marquesan speakers use this system in both large scale and small scale directional referencing.

“For a speaker of Marquesan it is not unusual to say that the plate on the table is inland of the

glass or to localize a crumb on another person’s cheek as being on the seaward or inland cheek.”

(Cablitz p.41)

References

Aryawibawa, I Nyoman. 2008. Semantic Typology: Semantics of Locative Relations in Rongga (ISO 639-3: ROR). Masters Thesis. University of Kansas

Bowerman, Melissa. 1999. Learning How to Structure Space for Language: A Crosslinguistic Perspective. In P. Bloom, M. A. Peterson, L. Nadel and M. F. Garrett (eds.), Language and Space, 385-436. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Brown, Penelope. 1994. The INs and ONs of Tzeltal locative expressions: The semantics of stative descriptions of location. Linguistics 32.4/5.743-790.

Brown, Penelope. 2001. Learning to talk about motion UP and DOWN in Tzeltal: is there a language-specific bias for verb learning? In M. Bowerman and S. C. Levinson (Eds.), Language Acquisition and Conceptual Development, 512-543. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cablitz, Gabriele H. 2002. The acquisition of an absolute system: learning to talk about SPACE in Marquesan (Oceanic, French Polynesia). The Proceedings of the 31st Stanford Child Language Research Forum, pp. 40-49.

Frawley, William. 1992. Linguistic Semantics. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Herskovits, Annette. 1986. Language and Spatial Cognition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hill, Clifford. 1974. Spatial perception and linguistic encoding: A case study of Hausa and English. Studies in African Linguistics (Supplement) 5.135-148.

Hill, Clifford. 1982. Up/Down, front/back, left/right. A contrastive study of Hausa and English. In J. Weissenborn and W. Klein (Eds.), Here and There, 13-42. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Kaufman, Terrence. 1990. Algunos rasgos estructurales de los idiomas Mayances con referencia especial al K’iche’. In N. C. England and S. R. Elliot (Eds.), Lecturas Sobre La Lingüistica Maya, 59-114. La Antigua Guatemala: CIRMA.

Levinson, Stephen C. 1996. Frames of Reference and Molyneux’s Question: Crosslinguistic Evidence. In P. Bloom, M. A. Peterson, L. Nadel and M. F. Garrett (eds.), Language and Space, 109-170. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Levinson, Stephen, Sérgio Meira, and The Language and Cognition Group. 2003. ‘Natural concepts’ in the spatial topological domain—adpositional meanings in crosslinguistic perspective: An exercise in semantic topology. Language 49.485-516.