|

|

Aspectual Classes

As we noted before, Carlotta Smith (1991) defined two main parameters of aspect:

1. Lexical Aspect (Aktionsart) - the aspectual classes of predicates

2. Event Perspective–the view of the entire event

In this section we will explore properties of lexical aspect in more detail. Kearns discusses three characteristics which are used to classify events:

1. A bounded or telic event has a natural end point or bound at which the event is finished. Unbounded or atelic events lack a natural end point.

Examples:

telic: eat a sandwich, water the garden, walk to school

atelic: eat, drink water, walk in the park

2. A durative event unfolds over a measurable time span as opposed to nondurative events which occur in an instant.

Examples:

durative: eat, water the garden, play a sonata

nondurative: find a penny, notice a dog, hiccup

3. A static or homogeneous event has no internal change. Dynamic or heterogeneous events mark some type of change in their participants.

Examples:

static: love linguistics, be tall, have a cow

dynamic: become a nurse, ask a question, play in the park

Smith uses these dimensions to distinguish five types of events:

|

|

Dynamic |

Durative (interval) |

Telic (result) |

Examples |

|

State |

-a |

+a |

- |

hot, have, like |

|

Activity |

+ |

+a |

- |

run, push a cart |

|

Accomplishment |

+ |

+a |

+a |

build a house |

|

Achievement |

+ |

- |

+a |

reach, spot, find |

|

Semelfactive |

+ |

- |

- |

knock, cough |

States are unbounded or atelic events since they lack a natural end point. The sentence Martha has a sandwich is an example of a stative event. The sentence does not specify a point at which Martha’s ownership of the sandwich ends, although a knowledge of people and sandwiches suggests that such a point exists.

States are durative since they continue over some interval of time. We can safely assume that Martha has had the sandwich for more than a nanosecond.

States are also static. Our saga of Martha and her sandwich only specifies that Martha is in possession of the sandwich, and does not imply that this possessive relationship is changing in any manner.

Activities are also unbounded and durative like states, but they specify some type of dynamic change to their participants. The sentence Harold pushed the cart is an example of an activity. Pushing takes place over a measurable interval, and the sentence does not state if Harold stopped pushing. The pushing activity is dynamic because Harold had to exert some force, which usually results in moving the cart.

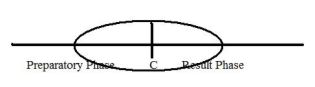

Accomplishments are dynamic and durative like activities, but result in some accomplishment. The sentence Janet washed the dishes is an accomplishment sentence. Dishwashing requires some interval of time, and should result in a dynamic change from dirty to clean crockery. The change in cleanliness for all the dishes marks the end of the accomplishment. Accomplishments usually have a preparatory phase (= an activity), a result state, and a culmination point at which the result state comes into being.

|

|

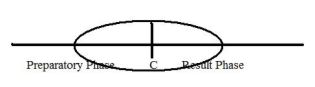

Achievements are abrupt forms of dynamic events. They result in a change of state like accomplishments, but achievements unfold in an instant. A good way to remember the difference between achievements and accomplishments is to note the word achievement is shorter than the word accomplishment. The sentence Clive found his keys illustrates an achievement. The act of finding unfolds in an instant; it’s the searching activity that takes much longer.

|

|

Some achievements are interpreted as having a preparatory phase. Reaching the summit, winning the race, arriving at the station, and dying are examples of achievements with preparatory phases.

Smith discusses a fifth class of event types—the semelfactives. Semelfactives, like achievements are abrupt forms of dynamic events. They differ from achievements in that semelfactives do not result in an accomplishment or change of state. The sentence Lucy coughed during rehearsal is an example of a semelfactive event.

|

|

Kearns notes that all of these predicates are referred to as eventualities. She adds that:

the classifications do not apply directly to eventualities themselves, but really to eventualities under a particular verb phrase description. An eventuality taken in itself may be described in different ways which place it in any of the four classes, depending on the verb phrase chosen to describe it or present it for attention. (156)

8.2. Testing for aktionsarten

The bounded/unbounded distinction in English becomes apparent with adverbial phrases that specify a time interval. Bounded events (accomplishments and achievements) can be completed within a finite period of time. Sentences with bounded predicates are acceptable with adverbial phrases like in a minute, within a day.

Accomplishments

Janet washed the dishes in half an hour.

Oliver ate the meat pie in 60 seconds.

Achievements

Clive found his keys in a minute.

Jake recognized her voice in a second.

The meaning of unbounded predicates clash with the usual interpretation of in adverbials. In such contexts, unbounded predicates can be given an alternative or ‘repair’ reading in which the in adverbial specifies the time at which the action or state begins. Such a reading is compatible with the future tense.

States

Martha will have a sandwich in a minute.

Abe will be happy in a year.

Activities

Harold will push the cart in half an hour.

Jason will live with Donald in another month.

Semelfactives

Lucy will cough in a minute.

The screen will flicker in another hour.

The simple past tense results in anomalous sentences:

States

#The couple were happy in two years.

#The room was sunny in an hour.

Activities

#They walked in the park in half an hour.

#Ralph pushed the cart in a minute.

Unbounded predicates (states, activities and semelfactives) are not completed in a finite stretch of time. Sentences with unbounded predicates are acceptable with adverbial phrases like for a minute, for two weeks.

States

Martha had a sandwich for a minute.

Abe was happy for a year.

Activities

Harold pushed the cart for a minute.

Jason lived with Donald for a year.

Semelfactives

Lucy coughed for a minute.

The screen flickered for an hour.

For adverbials produce different interpretations with bounded predicates.

Accomplishments

Janet washed the dishes for an hour.

Oliver ate the meat pie for a couple of minutes.

Achievements

Clive found his keys for a minute.

Jake recognized her voice for a minute.

With the accomplishment examples, the for adverbial induces an activity reading for the predicate which specifies the duration of the activity, but leaves the action incomplete. In the case of the achievement examples, the for adverbial measures the duration of the result state. Clive has his keys for a minute before misplacing them again.

8.2.4 The sub-interval property

It helps to think of how eventualities unfold over an interval of time. Telic events have beginning and end points.

eat a sandwich |______________________________|

start finish

Ie = event time |_______[.............Is...............]_______|

Is = sub-interval [............................Ie.............................]

The event of eating a sandwich unfolds over the interval Ie, and is completed when the sandwich is eaten. The sub-interval Is measures out part of the eating process, but doesn’t include the end point. While the end state ate a sandwhich is true at the end of Ie, it is not true at the end of Is. The sub-interval is best described by the progressive eating a sandwich.

Atelic events have a different sub-interval property.

walk the dog |______________________________|

start finish

Ie = event time |_______[.............Is...............]_______|

Is = sub-interval [............................Ie.............................]

For atelic events, the sub-interval has all of the properties of the event interval (ideally). That is, walked the dog is true of both the sub-interval as well as at the end of the event interval. Kearns refers to this condition as the sub-interval property.

These differences can be diagramed on a time line.

|.........................................|

t1 t2

in adverbials: the interval t1 - t2

States: t2 = onset of the state

Activities: t2 = onset of the activity

Accomplishment: t2 = endpoint of the action

Achievement: t2 = onset and endpoint of the action

for adverbials:

States: t2 = time within the state; part of its duration

Activities: t2 = time within the activity; part of its duration

Accomplishment: t2 = time within the activity; the action is incomplete

Achievement: t2 = endpoint of the result state

The take+time construction is most natural with accomplishments. It induces an accomplishment reading with the other predicate types.

What is an Interval?

First we need to assume an ordered set of points on a time line T. I is an interval iff I ⊂ T and for all moments in time t1, t2, t3, if t1, t3 ∈ I, and t1 ≤ t2 ≤ t3, then t2 ∈ I.

A closed interval [t1 , t2] is defined as {t: t1 ≤ t ≤ t2} (the end points are included)

A bounded interval (t1 , t2) is defined as {t:t1 < t < t2} (the end points are excluded)

A moment [t] abbreviates the closed interval [t , t] that contains a single point, i.e., {t}

Dowty (1979) defines the truth conditions for [BECOME φ] relative to an interval I as:

[BECOME φ] is true at I iff there is an interval J containing the initial bound of I such that ¬ φ is true at J and there is an interval K containing the final bound of I such that φ is true at K.

______J______ ______I______ ______K______

............[........................]..........................[.........................]...........>

~ φ is true [BECOME φ] φ is true

This statement doesn’t impose any constraints on the truth value of φ in I other than on the two endpoints of I. I can be any length of time you chose. Such a case doesn’t satisfy our intuitions about changes of states. The sentence ‘the door opens’ is not true for any arbitrary interval, rather we evaluate the truth of the sentence relative to the smallest interval over which the change of state takes place.

~ φ is true φ is true

......[................[...........[............|.............].............]............]...........>

[______I______]

[____________I’_____________]

[_____________________I’’___________________]

Thus, we need to change to a stronger definition of the truth conditions for [BECOME φ]:

[BECOME φ] is true at I iff (1) there is an interval J containing the initial bound of I such that ¬ φ is true at J, (2) there is an interval K containing the final bound of I such that φ is true at K, and (3) there is no non-empty interval I’ such that I’ ⊂ I and conditions (1) and (2) hold for I’ as well as I.

This definition is too strong! You don’t want to assert that building a house is only true for the last interval marking the completion of the house. Also get a problem with a sentence like

John walked from the Post Office to the Bank

____P & ~ B__ __~ P & ~ B___ ___~ P & B___

............[.......................]..........................[..........................]...........>

[______I______][______J______]

We do not want the interval BECOME[¬P ^ B], i.e., just before John gets to the Bank. Instead we need the truth condition to be [BECOME ¬P] ^ [BECOME B]. Dowty observes that the strict interpretation of [BECOME φ] is true only if John doesn’t take longer than a moment to get from the Post Office to the Bank. It might be better to interpret the third condition as a conversational principle rather than a strict condition on the truth of [BECOME φ].

9.2.2 Static and Dynamic

The aspectual classes of predicates interact differently with various tenses and aspects. State predicates have a natural interpretation in the present tense, while dynamic predicates induce special readings such as the habitual or the historic present.

States

Martha has a sandwich.

He believes this rubbish.

The house stands on the bluff overlooking the beach.

Non-states

George runs in the park.

Mary writes poetry.

He notices the little details.

Only dynamic predicates allow the progressive in many English dialects. State predicates in these dialects resist use with the progressive.

States

Martha is having a sandwich.

*Harry is knowing Tiriyó.

*We are being in London.

Non-states

George is running in the park.

Mary is writing poetry.

?He is noticing the scratch on the car.

Some stative predicates can be used in the progressive, in which case they denote a more temporary state.

22a. We live in Berlin.

b. We are living in Berlin.

c. The statue stands in front of Lippincott.

d. The statue is standing in front of Lippincott.

8.5 Agentivity

Some contexts that select for agents are also sensitive to aspectual distinctions between predicates. Agents are required in the complement to persuade, with adverbs like carefully,

deliberately, conscientiously, in the imperative mood, and in the what x did construction.

Accomplishments and activities can be used in these agentive contexts, but achievements and states cannot.

Complement of persuade

Accomplishments

I persuaded Janet to wash the dishes.

They persuaded Oliver to eat the meat pie.

Activities

I persuaded Harold to push the cart.

Sam persuaded Jason to work with Donald.

States

I persuaded Martha to have a sandwich.

Kent persuaded Abe to be happy.

Achievements

*I persuaded Clive to find his keys.

*Sally persuaded Jake to recognize her voice.

Semelfactives

I persuaded Lucy to cough.

?We persuaded the screen to flicker.

Agentive adverbs

Accomplishments

Janet carefully washed the dishes.

Oliver deliberately ate the meat pie.

Activities

Harold deliberately pushed the cart.

Jason carefully worked with Donald.

States

?Martha deliberately had the sandwich.

?Abe is happy deliberately.

Achievements

?Clive deliberately found his keys.

?Jake deliberately recognized her voice.

Semelfactives

Lucy deliberately coughed.

?The screen deliberately flickered.

Imperative Mood

Accomplishments

Wash the dishes!

Eat the meat pie!

Activities

Push the cart!

Work with Donald!

States

Have a sandwich!

Be happy!

Achievements

Find his keys!

?Recognize her voice!

Semelfactives

Cough!

?Flicker!

What x did construction

Accomplishments

What Janet did was wash the dishes.

What Oliver did was eat the meat pie.

Activities

What Harold did was push the cart.

What Jason did was work with Donald.

States

What Martha did was have a sandwich.

?What Abe did was be happy.

Achievements

What Clive did was find his keys.

?What Jake did was recognize her voice.

Semelfactives

What Lucy did was cough.

What the screen did was flicker.

States can be agentive if they allow volition or control of the state.

28a. What you must do is be absent that day.

c. I was deliberately absent that day.

d. * He’s being absent today.

Kearns suggests the agentivity of some predicates depends on whether or not they have a human participant.

29a. What Jones is doing is lying on the floor.

b. * What the newspaper is doing is lying on the floor.

An example in Dowty (1991:560) shows that agentivity is not the complete answer.

The rowboat is lying on the river bank.

* New Orleans is lying at the mouth of the Mississippi River.

9.2.4 Internal Complexity

Certain contexts bring out contrasts in the internal complexity of the aspectual classes. The verb finish selects complements that involve both duration and an endpoint, i.e., accomplishments.

Janet finished washing the dishes.

Jason finished working with Donald.

*Martha finished having the flu.

*Clive finished finding his keys.

Lucy finished coughing.

The adverb almost also interacts with the internal complexities of the aspectual classes in different ways.

State

Martha almost had the flu.

a. Past Almost ∃s (HAVE FLU(s) & THEME(m,s))

‘There almost was a state and the state would have been having the flu and Martha would have been the theme of the state.’

b. Past ∃s (Almost HAVE FLU(s) & THEME(m,s))

‘There was a state and the state was almost having the flu and Martha was the theme of the state.’

Activity

Harold almost pushed the cart.

a. Past Almost ∃e (PUSH(e) & AGENT(h,e) & THEME(c,e))

‘There almost was an event and the event would have been pushing and Harold ...’

b. Past ∃e (Almost PUSH(e) & AGENT(h,e) & THEME(c,e))

‘There was an event and the event was almost pushing and Harold ...’

Achievement

Clive found his keys.

a. Past Almost ∃e (FIND(e) & EXPERIENCER(c,e) & STIMULUS(his keys,e))

‘There almost was an event and the event would have been finding and Clive ...’

Accomplishment

Janet washed the dishes.

a. Past Almost ∃e (WASH(e) & AGENT(j,e) & PATIENT(the dishes,e))

‘There almost was an event and the event would have been washing and Janet ...’

b. Past ∃e (Almost WASH(e) & AGENT(j,e) & PATIENT(the dishes,e))

‘There was an event and the event was almost washing and Janet ...’

c. Past ∃e (WASH(e) & AGENT(j,e) & Almost PATIENT(the dishes,e))

‘There was an event and the even was washing and Janet ... and the dishes were almost

(all) the patient of the event.’

8.2.5 Progressives

The English progressive focuses on the activity segment of events. The progressive converts accomplishments into activities by highlighting the activity involved.

Janet was washing the dishes for an hour.

?Janet was washing the dishes in an hour.

Accomplishment predicates in the progressive no longer entail the completion of the event. Compare the entailments with an accomplishment and activity.

‘Janet was washing the dishes’ does not entail ‘Janet washed the dishes’.

‘Harold was pushing the cart’ entails ‘Harold pushed the cart’.

Achievement predicates are anomalous with the progressive since they lack an activity portion of the event for the progressive to highlight.

?Clive was finding his keys when his mother sneezed.

?Jake was recognizing her voice when the phone rang.

Some achievement predicates have a natural interpretation with progressives.

38. Bill was winning for the first few laps.

Lauren was dying for months.

They are reaching the summit now.

The train is now arriving at Track No. 3.

Other tests suggest that these predicates are achievements. They probably belong to a separate aspectual class of predicates.

Progressives of semelfactive predicates highlight the event’s repetition.

39. Lucy was coughing.

The screen was flickering.

The Imperfective Paradox

Dowty (1979: 133) draws attention to a major difference between activities and accomplishments in the progressive, e.g.,

1. John was pushing a cart [entails] John pushed a cart

2. John was drawing a circle [does not entail] John drew a circle

Accomplishment verbs are telic, they describe activities that normally lead to a result

Yet the result is not accomplished when the phrase appears in the progressive aspect

How do we account for the feeling that John was engaged in a bringing-a-circle-into-existence activity and yet might not have brought a circle into existence? This is the ‘imperfective paradox’. We could just as easily say that he was bringing a triangle into existence.

John was drawing a horse =? John was drawing a unicorn.

Could try an approach that relies on the intentions of the agent (he intends to draw a circle)

Non-sentient agents create a problem:

The drought is destroying the crops.

The river is undercutting its banks.

Formally, we want a theory that derives the meaning of [PROG φ] from the meaning of φ, i.e. compositionally. In the case of accomplishments however, the progressive meaning requires access to the parts of the accomplishment. If an accomplishment verb is represented as

[ψ CAUSE [BECOME χ]], PROG [ψ CAUSE [BECOME χ]] must entail ψ but not entail [BECOME χ] even though [ψ CAUSE [BECOME χ]] entails both ψ and [BECOME χ].

Although most achievement verbs do not occur in the progressing (??John was finding his keys), the few that do create the same problems as the accomplishment verbs:

John was falling asleep [does not entail] John fell asleep

Mary was dying [does not entail] Mary died

The paradox occurs in part because semantic theories link the truth of an atomic sentence to a moment in time rather than an interval of time. An interval is not simply a set of moments, otherwise the expressions would be equivalent, e.g., ∀t [t ∈ one week → AT(t, φ)].

This notion works for stative predicates, e.g., John lived in Boston for years.

But not for activities, e.g., John spent an hour working on his tax return.

He might have taken a break for five minutes

The truth of the sentence is relative to the interval, not necessarily every moment on the interval.

Possible Worlds

Dowty resorts to the use of possible worlds to spell out the connection between drawing a circle and the resulting circle. In other words the circle is a possible outcome of John’s activity. This approach implies that the progressive is not solely an aspectual operator, but rather a mixed modal-aspectual operator. Dowty proposes the following analysis:

[PROG φ] is true at <I, w> iff there is an interval I’ such that I ⊂ I’ and I is not a final subinterval for I’ and there is a world w’ for which φ is true at <I’, w’>, and w is exactly like w’ at all times preceding and including I.

¬ ψ is true I’ ψ is true

w’ ------------------|-]-------------[----------------]---------------[-|------------]-------->

I |

w ----------------------------------[----------------]--------------------------------------->

PROG [BECOME ψ] is true

The two lines labeled w and w’ represent, respectively, the course of time in the actual world and in some possible world. The dotted line connecting the two time lines indicates the point up to which w and w’ are exactly alike.

This analysis does not require ψ to be true at any time in the actual world w (although it does not exclude this possibility), but it does require that some initial subinterval of the coming about of ψ be ‘actualized’. It also requires that there be a time in the past in the actual world at which ¬ ψ was true.

Dowty’s truth condition relative to possible worlds entails that the following sentences are both true.

The coin is coming up heads.

The coin is coming up tails.

Evidently, an even stronger condition is needed. Dowty offers a suggestion from David Lewis that the truth be relative to the set of worlds in which the “natural course of events” takes place. That is to say, all the worlds in which nothing untoward disrupts the natural inertia of the event. Dowty suggests enriching the logic with a set of inertia worlds which are exactly like the given world up to the time in question and in which the future course of events after this time develops in ways most compatible with the past course of events.

Dowty’s final attempt at the truth conditions for [PROG φ] is thus:

[PROG φ] is true at <I, w> iff for some interval I’ such that I ⊂ I’ and I is not a final subinterval for I’, and for all w’ such that w’ ∈ Inertial World(<I, w>), φ is true at <I’, w’>.

Compare

John was watching television when Bill entered the room.

John was watching television when he fell asleep.

The sentences show that the real entailment from progressives is the possibility that John

continue the watching, not that it actually continues.

8.6 Countability and Boundedness

The bounded/unbounded predicate contrast has some intriguing parallels with contrasts between various noun classes. Singular count nouns produce bounded predicates while bare plurals produce unbounded predicates.

Singular count noun

She ate an apple.

He played a sonata.

Bare plurals

She ate apples.

He played sonatas.

The noun phrase serving as the direct object in these sentences determines a natural bound for the action. The eating event is over when the food is consumed. Dowty (1991) named the nouns in these semantic roles incremental themes since their state measures the completion of the action. With the bare plurals as direct objects, the same predicates denote semelfactive events.

Mass nouns also produce unbounded predicates. Rather than denoting a series of separate events, mass nouns result in a single, unbounded event.

48e. Sand fell on the roof all morning.

He played music from the Italian renaissance all evening.

Adverbial phrases can be attached to unbounded events to specify an endpoint or bound for the event in the same way that measure phrases can be added to specify a finite quantity of a substance. Both additions add a boundary to the event or the substance.

40a. a block of cheese

b. a slice of cake

d. walk to the corner

e. beat the eggs to a froth

These examples show that the aspectual classes are determined by the semantic properties of the whole sentence, and not just by the properties of the verb, although the verb can restrict the possible interpretations that are produced with different adverbial modifiers.

Analyzing the Internal Structure of Events

We have used two schemes representing the internal structure of events:

Janet is washing the dishes.

Neodavidsonian

∃t ∃e (t = t* & WASH(e) at t & AGENT(j,e) & PATIENT(the dishes,e))

‘There was an event and the event is washing and it is now and Janet ...’

Dowty (1979)

PROG [DO (j) [CAUSE [BECOME [WASHED (the dishes)]]]]

We have also identified a number of tests that we can use to test these schemes. We can apply these tests to these schemes to identify the strengths and weaknesses of each approach. Keep in mind that a better approach might be to combine elements from each of these schemes.

Tests

1. Argument Entailments

One test that supports Davidson’s approach is derived from argument entailment. Since Davidson represents the components of an event as conjoined elements he can derive an entailment from the conjoined set to a subset, e.g.

Janet is washing the dishes.

entails:

Janet is washing. (Dropping the Patient)

The dishes are being washed. (Dropping the Agent)

There is a washing event (Dropping both Agent and Patient)

We can derive the same entailments from Dowty’s scheme, but the derivation is less direct. In other words, we have to enrich Dowty’s approach in order to derive the entailments. We can translate Dowty’s DO predicate as Davidson’s event variable e. We can then derive the entailment that a washing event occurred by combining the components:

[DO [BECOME [WASHED ()]]]

In order to reach this entailment, we have to assume that the particular event taking place is one that changes the state of the patient to a washed state. This assumption requires the particular state WASHED to enrich the inchoative predicate BECOME to derive the entailment:

[BECOME [WASHED ()]] —> WASHING()

If we state this assumption as a meaning postulate then we can derive Davidson’s entailment from Dowty’s scheme as well as show precisely how we have to enrich Dowty’s approach.

We can derive the entailment that dishes are being washed from Dowty’s scheme with the understanding that the patient is represented as the theme of the state change denoted by the inchoative predicate BECOME. Likewise, we can derive the entailment that Janet is doing the washing from the fact that Janet is the first argument of the event predicate DO.

2. Adverbial Tests

Kearns shows how adverbs like almost target different components of an event using the Neodavidsonian schema.

Janet is almost washing the dishes.

a. ∃t Almost ∃e (t = t* & WASH(e) at t & AGENT(j,e) & PATIENT(the dishes,e))

‘There is almost an event and the event is washing and Janet ...’

b. ∃t ∃e (t = t* & Almost WASH(e) at t & AGENT(j,e) & PATIENT(the dishes,e))

‘There is an event and the event is almost washing and Janet ...’

c. ∃t ∃e (t = t* & WASH(e) at t & AGENT(j,e) & Almost PATIENT(the dishes,e))

‘There is an event and the event is washing ... and the dishes were almost (all) the patient of the event.’

Applying the almost test to the progressive event produces results that are different from applying the test to past events. Compare the progressive event with the past event:

Janet is almost washing the dishes.

Janet almost washed the dishes.

For past tense events we can imagine a situation in which Janet had every intention of washing the dishes but decided to go to the library instead. This provides an interpretation for reading (a) the almost event sense. This reading is not available in the progressive since the progressive puts us into the middle of the washing event, which contradicts the almost event reading. We can assume that the assertion Almost ∃e is contradicted by the assertion ∃t (t = t* & WASH(e) at t), that is, ‘there is almost an event and the event is taking place now.’

The other readings hold for both the progressive and the past.

Applying the almost test to the Dowty framework produces the following representations:

a. PROG [ALMOST DO (j) [CAUSE [BECOME [WASHED (the dishes)]]]]

PROG [DO (j) [ALMOST CAUSE [BECOME [WASHED (the dishes)]]]]

PROG [DO (j) [CAUSE [ALMOST BECOME [WASHED (the dishes)]]]]

b. PROG [DO (j) [CAUSE [BECOME [ALMOST WASHED (the dishes)]]]]

c. PROG [DO (j) [CAUSE [BECOME [WASHED (ALMOST the dishes)]]]]

The almost test produces more readings in Dowty’s framework since his approach provides more details of the internal structure of events. We could apply the adverb to the PROG operator to produce an ALMOST PROG reading, but I am not sure what interpretation to give this combination, that is, I am not persuaded that the past, habitual or future provide an appropriate interpretation for ALMOST PROG. We might assume a general semantic constraint exists that prevents an adverb like almost from modifying tense or aspect.

Interpreting the DO predicate as Davidson’s event variable produces the (a) reading discussed above. The other two Neodavidsonian readings are shown as (b) and (c) above. This leaves two senses that are not predicted by the Neodavidsonian scheme. In the first case, Janet does something that is an almost causal event. This reading corresponds to a situation where Janet goes through the motions but they are not causal, she almost cleaned the dishes but didn’t use detergent. In the second case, Janet is causing the dishes to almost become washed but they still remain dirty. This sense is different from the sense in (b) where the inchoative predicate applies, but Janet is not washing, she’s rinsing.

I conclude that the almost test gives more support to Dowty’s analysis.

3. The Imperfective Paradox

We can apply the test of imperfective entailment to the Neodavidsonian and Dowty schemes to see which, if any, predicts the lack of entailment for the progressive. I provided a somewhat simple translation of the progressive to the Neodavidsonian representation:

∃t ∃e (t = t* & WASH(e) at t & AGENT(j,e) & PATIENT(the dishes,e))

‘There is an event and the event is washing and it is happening now and Janet ...’

If all of the conjuncts in this representation are true then we can conclude:

There is a washing event

Janet is the Agent

The dishes are the Patient

Assuming that the Patient role indicates the dishes are affected by the washing, we derive the false entailment that ‘Janet is washing the dishes’ entails that she washed the dishes. What seems to be going wrong here is applying the Patient role to all of the dishes. The Neodavidsonian representation doesn’t let us apply the Patient role to some of the dishes.

Applying the progressive to Dowty’s scheme produces the representation:

PROG [DO (j) [CAUSE [BECOME [WASHED (the dishes)]]]]

As discussed by Dowty, there is no obvious way to block the entailment to

BECOME [WASHED (the dishes)]

Again we note that the difficulty arises from applying the WASHED predicate to the dishes collectively rather than distributively. We need a way to apply the PROG operator to the inchoative predicate BECOME, something like:

[DO (j) [CAUSE [PROG BECOME [WASHED (the dishes)]]]]

We could assume that the PROG operator only applies to the lowest event predicate rather than to the event and causal predicates. The progressive extends the duration of the inchoative, that is the change from the unwashed to the washed state, eliminating the final result state. Effectively, the progressive points to a point in time that is internal to the interval of the state change. Dowty’s interpretation of this state change as one from ¬ ψ to ψ does not leave any room for halfway states. A more realistic interpretation of state changes would take the form of an algebraic formula: y = mt, where m provides the gradient and t the time. This interpretation doesn’t have an upper or lower boundary so it doesn’t offer a very realistic interpretation. What is needed is something akin to a growth equation with upper and lower asymptotes, e.g.

dy/dt = ry (1 - y/K)

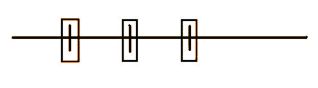

In this equation r represents the reproductive rate and K is the carrying capacity of the resource. It results in a sigmoid curve

|

|

With this enrichment of Dowty’s framework, we derive the result that PROG BECOME [WASHED (the dishes)] does not entail BECOME [WASHED (the dishes)]. BECOME [WASHED (the dishes)] does not become true until the upper bound is reached when all the dishes are reached. The PROG operator locates the event at a point before the upper bound.

I conclude that Dowty’s schema provides a better framework for representing events since it predicts readings that the Neodavidsonian framework does not predict and since it can be enriched to account for the imperfective paradox.

Exercises

Kearns (p. 226)

Place Adverbials

Some place adverbials denote places filled by substances or by events which are spatially extended, e.g.

1. There’s mud all over the floor.

2. The combatants rolled all over the floor.

3. There’s heavy fog throughout the state.

4. The war raged throughout the state.

Write a Neodavidsonian formula for these sentence using the variable l to represent locations and AT(e,l) to express ‘e occupies location l’.

Write two different expressions that represent the interpretations for the sentence

Throughout the state the local newspaper is successful.

Kearns (p. 248)

(A) Use Dowty’s schema to interpret the following sentences

1. Peter ran inside.

2. Simon was hungry.

3. Charlie flew the kite into the tree.

4. Mary made Lucy laugh.

5. Padmini ground the spices to powder.

6. The wood half burned.

7. Jones left Paris.

8. The car left the road.

Kearns (p. 249)

(C) Verbs of Eating

The following sentences show a difference between nibble and swallow.

1.a. Bugs nibbled the lettuce leaf.

b. # Bugs nibbled the lettuce leaf down.

c. Bugs nibbled at the lettuce leaf.

2.a. Benjamin swallowed the pill.

b. Benjamin swallowed the pill down.

c. # Benjamin swallowed at the pill.

What Patient macrorole factors are present in the following underlined NPs?

Bugs nibbled the leaf.

Bugs nibbled at the leaf.

Benjamin swallowed the pill.

Benjamin swallowed the pill down.

References

Bennett, Michael & Barbara Partee. 1978 (1972). Toward the logic of tense and aspect in English. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Linguistics Club.

Dowty, David. 1979. Word Meaning and Montague Grammar. Dordrecht: Reidel.

—–. 1991. Thematic proto-roles and argument selection. Language 67:547-619.

Smith, Carlota S. 1991. The Parameter of Aspect. Dordrecht: Kluwer.