Intensional Objects

In the book Naming and Necessity, Kripke discusses the meaning of words that are introduced by definition. A meter, for example, was defined by reference to the length of a certain bar S in Paris. The kilogram, likewise, is defined by the weight of a certain lump of metal in Paris.

The difficulty with such definitions is that real objects change their properties over time, whereas the concepts referred to by the words meter and kilogram are expected to have uniform properties no matter what external factors are in play, e.g. the time, temperature, humidity, air pressure, phase of the moon, etc.

Kripke distinguishes the use of the bar S to give the meaning of meter from its use to fix the reference of meter. Kripke states that fixing the reference of meter is accomplished by reference to an accidental property of the bar S. Kripke claims that the word meter rigidly designates a certain length in all possible worlds, which in the actual world happens to correspond to the length of the bar S. On the other hand, the phrase ‘the length of the bar S’ does not designate rigidly. Kripke means that the length of a physical bar S can be expected to vary due to all sorts of external factors.

We have discussed this distinction earlier in terms of the contrast between a word’s extension and its intension. The extension of meter would be the length equal to that of the bar S, whereas the intension of meter would be a fixed length in all possible worlds (and not the length of the bar S in all possible worlds). We can borrow a notational device from Montague Semantics and use meter to refer to the word’s extension and meter' to refer to the word’s intension.

Biological Nomenclature

Scientific terms provide a rich set of examples that illustrate the distinction between extension and intension. The general approach is to use an accidental correspondence to some object to fix the reference of a scientific ideal. The Linnaean system of nomenclature is established on the basis of this correspondence. Linnaeus’s system begins with the definition of a species as the basic biological unit. As described by Stephen Jay Gould:

Linnaeus’s binomial method has been used, ever since his Systema Naturae (first edition published in 1735, definitive edition for animal taxonomy in 1758), as the official basis for naming organisms. Linnaeus gave each species a two-word (or binomial) name, the first (with a capital letter) representing its genus (and potentially shared with other closely related species), and the second (called the trivial name and beginning with a lowercase letter) as the unique and distinctive marker of a species. (Dogs and wolves both reside in the genus Canis, but each must have a separate trivial name to designate the species—Canis familiaris and Canis lupus respectively, in this case.) (1995:421-422).

Gould notes that Linnaeus’s system derives from a pre-existing convention of naming species by a string of Latin words that list their distinctive features. (In this system, the first word was capitalized since it comes at the beginning of the phrase!) Note how the pre-existing naming convention used the description to give the meaning of the name.

Linnaeus simplified this system by shortening the phrase to just two words. At first he regretted jettising the previous convention of using descriptive phrases, but he eventually realized his binomial convention establishes a name for each species rather than a description. Gould is fond of noting that Linnaeus’s name for his own species (Homo sapiens) was one of his biggest mistakes.

The accidental component enters the Linnaean system through the use of type specimens. Each name in Linnaeus’s system is attached to a specimen housed in a natural history collection somewhere—“a single preserved creature that becomes the official name-bearer for the species” (279). The type specimen for Gould’s favorite snail, Cerion uva, resides in the Linnean Society’s Burlington House, on Piccadilly in the center of London. Linnaeus, himself, established Cerion uva as the type species of the genus of snails on the basis of this specimen. Gould observes:

We need such types because we often later discover that a named “species” really includes specimens from two or more legitimate species. We must then retain the original name for one of those species, and coin new designations for the others. But which population gets to keep the old name? By the rules of nomenclature, the original name belongs to the type specimen in perpetuity—and its population retains this first designation. (p. 279)

The beauty of the Linnaean system is that it provides a systematic procedure that responds to the discovery of accidental designations.

Artifacts

Artifacts provide another illustration of the distinction between extension and intension. The old engineering adage maintains that form follows function. Supposedly, the purpose of any artifact is to serve some function, and some forms are ideally suited to each function. The purpose defines the intension of the artifact, whereas its form defines the extension of the artifact.

The function that is supposed to give rise to form is ridiculed by engineers. David Pye maintains that “function is a fantasy” and adds:

The concept of function in design, and even the doctrine of functionalism, might be worth a little attention if things ever worked. It is, however, obvious that they do not. Indeed, I have sometimes wondered whether our unconscious motive for doing so much useless work is to show that if we cannot make things work properly we can at least make them presentable. Nothing we design or make every really works. We can always say what it ought to do, but that it never does. The aircraft falls out of the sky or rams the earth full tilt and kills the people. It has to be tended like a new born babe. It drinks like a fish. Its life is measured in hours. Our dinner table ought to be variable in size and height, removable altogether, impervious to scratches, self-cleaning, and having no legs.... Never do we achieve a satisfactory performance... Every thing we design and make is an improvisation, a lash-up, something inept and provisional.

Henry Petroski has written a series of books and articles that illustrate how the interplay between form and function leads to the evolution of artifacts. The telephone illustrates how an artifact changes to fulfill an original function better as well as in reaction to external factors.

|

|

|

|

|

|

What was the phone’s original function?

How was this function connected to its form?

What did the rotary dial contribute to the phone’s function?

How did push buttons improve on the rotary dial?

What did the cordless phone add in functionality?

Is the iphone a phone?

The extension of the word telephone continues to change over time as new technologies become available. A Fregean would assert that the intension of the word telephone remains unchanged. Borrowing Kripke’s discussion of meter, we can say that each implementation of a telephone helps to fix the reference of the word, but they do not define what constitutes a telephone. New telephone designs reveal different dimensions of the telephone’s potential.

Bare Plural NPs

Bare plural NPs are plural NPs that lack a determiner. People, cars, ideas, and fallacies are examples of bare plurals. Bare plurals behave differently from the other types of NPs we have analyzed. Bare plurals combine with predicates to produce existential and generic readings. Predicates denoting a temporary property produce an existential reading with bare plurals. Predicates that denote a lasting property produce a generic reading:

33. Existential reading

a. Firemen are available.

b. Teachers are patrolling the halls.

Generic reading

e. Firemen are altruistic.

f. Teachers are white-collar workers.

Kearns translates these readings into logic as:

35a. [∃x: FIREMAN(x)] AVAILABLE(x)

b. [∃x: TEACHER(x)] PATROLLING(x)

e. [Gen x: FIREMAN(x)] ALTRUISTIC(x)

f. [Gen x: TEACHER(x)] WHITE-COLLAR(x)

Gen represents generic quantification. Kearns’ generic treatment is a bit peculiar in that it literally translates as “generic firemen are altruistic”. Krifka (2004) suggests something like the following:

GEN ALTRUISTIC(FIREMEN)

Here, the generic quantifier can be interpreted as applying to possible worlds rather than individuals, i.e. GEN(w). The main question that Kearns is raising is whether bare plurals have a unique feature that interacts in different ways with different types of predicates.

Singular NPs can also have generic readings:

36a. Lilies are true bulbs.

b. The lily is a true bulb.

c. A lily is a true bulb.

Kearns suggests two approaches to accounting for the existential and generic readings for bare plurals found in (35). The first approach assumes that bare plurals incorporate an existential quantifier into the NP. This approach equates the sentence Firemen are available with the sentence Some firemen are available. Saying that bare plurals in such sentences contain existential quantification as part of the meaning of the NP is purely stipulative without independent evidence. Such an analysis fails to account for the difference between singular and plural NPs.

Another approach assumes that bare plurals contain a free variable that reacts to predicates in different ways. Active predicates contribute an existential quantifier while stative predicates contribute the generic operator. Kearns looks to quantificational adverbs for evidence in favor of one or another of these approaches. At this point, she does not examine whether bare plurals are different from definite and indefinite singular NPs in this respect.

There is a problem though. Kearns only examines bare plurals with stative predicates. What happens when we use bare plurals with non-stative predicates, e.g. Dogs are playing in the yard?

Bare Plurals and Quantificational Adverbs

Quantificational adverbs quantify over the times of an event:

37. Liam never / seldom / occasionally / sometimes / often / usually / always has breakfast.

These quantified times can be related to quantified Nps:

38. Adverb Quantified NP

never no mornings

seldom few mornings

occasionally a few mornings

sometimes some mornings

often many mornings

usually most mornings

always all mornings

Quantificational adverbs also seem to bind variables introduced by bare plurals. The following sentences show an ambiguity between a bound time reading and a bound variable reading:

39a. Dogs are often noisy.

Bound time: Dogs in general are noisy on many occasions.

Bound variable: [Many x: DOG(x)] NOISY(x) ‘Many dogs are noisy.’

b. Encyclopedias are usually expensive.

Bound time: Encyclopedias in general are expensive most of the time.

Bound variable: [Most x: ENCYCLOPEDIA(x)] EXPENSIVE(x) ‘Most encyclopedias are

expensive.’

c. Patients with this disorder seldom recover.

Bound time: Patients with this disorder in general recover on few occasions.

Bound variable: [Few x: PATIENT(x)] RECOVER(x) ‘Few patients with this disorder

recover.

This evidence supports the second analysis of bare plurals incorporating a free variable rather

than the first approach in which the bare plural contains an existential quantifier. The free variable analysis predicts that bare plurals will induce distributive readings in which the predicate applies separately to each individual rather than to the group or sum individual.

Generic NPs and Reference to Kinds

Kearns returns to the puzzle created by the generic reference by different types of NPs:

42a. Lilies are true bulbs.

b. A lily is a true bulb.

c. The lily ia a true bulb.

Reference to natural kinds produces one type of generic reference. A natural kind is a natural category of thing or substance. Mass substances such as gold and water, as well as animal and plant species such as tigers and lilies are natural kinds. Natural kinds may be referred to by scientific terms or by their common name:

43a. Canis familiaris is a popular pet.

c. The dog is a popular pet.

There are a few predicates that are closely associated with a natural kind as a group. Krifka (2004) labels these kind reference.

44a. The dodo is extinct.

b. The panda may die out.

Other predicates used with natural kinds apply to individual members of the group. Krifka labels these characterizing statements.

45a. The African grey parrot has a strong curved beak.

b. The kiwi lays enormous eggs.

This is similar to the ambiguity with nouns like paper that refer to either the object or the substance. Kearns then examines whether the singular definite NPs in (45) have the same interpretation as the bare plurals she discussed in the previous section. If so, they should display the same distributive interpretations as the bare plurals. Kearns discusses several arguments against a distributive (free variable) interpretation and in favor of an abstract kind individual interpretation of the singular definite NPs in (45).

1. The predicates in (45) can be given a kind interpretation by taking the properties of the individuals that make up the kind to define a kind individual, which acts as a substitute for reference to the group. We expect each member of the kind to display the characteristic properties of the group. This accounts for the distributive reading of the sentences in (45). A single abstract African grey parrot can stand in for the group.

2. Applying distributive predication to the members of a kind does not explain why characterizing statement can apply to some members of the group rather than to all of the members. Sentences like The hedgehog is affected by ringworm show that a tendency to display a given feature is sufficient to characterize the entire group, even though it is impossible to say what proportion of hedgehogs suffer from ringworm. This difficulty is avoided by attributing the property directly to the kind through a kind individual rather than to its individual members.

3. Generic NPs such as the teacher cannot be used in distributive (characterizing) contexts that are acceptable with bare plurals (51), singular collectives (52) and reciprocals like each other (53).

50a. Lions gather at the water-hole in the evening.

e. * The lion gathers at the water-hole in the evening.

51c. The family gathers for meals.

d. The family gather for meals.

52a. The family support each other.

b. Teachers support each other.

c. * The teacher support each other.

d. * The teacher supports each other.

These differences can be explained by assuming that singular definite NPs refer to some kind of individual rather than an expression with a free variable.

4. Bare plurals also contrast with generic singular definites in cumulative predication:

53a. Bulls have horns.

b. Unicorns have horns.

c. The bull has horns.

d. The unicorn has horns.

(53d) implies that unicorns have more than one horn so it is false. The unicorn in (53d) cannot be given a cumulative reading to allow the number of horns to increase with each additional member of the group, so the only option is the reading where a single unicorn has more than one horn.

5. Definite singular NPs sound odd if used generically for groups of objects that don’t constitute natural kinds:

54a. The Coke bottle has a narrow neck. (specific and generic)

b. A Coke bottle has a narrow neck.

c. Coke bottles have narrow necks.

d. * The green bottle has a narrow neck. (ok with specific interpretation)

e. A green bottle has a narrow neck.

f. Green bottles have narrow necks.

The generic interpretation of the definite singular NP in (54d) presupposes that a green bottle is a particular kind of bottle, which is not the case.

These arguments show that definite singular generic NPs denote an abstract single individual which has properties that are found on individual members of the kind. Indefinite singular generic NPs and bare plurals allow generalizations about individuals who fit a given description, even though they may not form a natural kind.

Indefinite singular NPs, like bare plurals, have existential readings with predicates denoting temporary properties, and generic readings with predicates denoting enduring properties:

56. Existential reading

a. A fireman is available.

b. A teacher is on duty

Generic reading

d. A fireman is altruistic.

e. A teacher is a white-collar worker.

Heim (1982) proposed treating singular indefinite NPs may be treated like bare plurals and bound by a quantifier in another part of the sentence. Kearns provides the following examples:

57a. A dog is often noisy.

‘Dogs are often noisy.’

[Many x: DOG(x)] NOISY(x)

b. An encyclopedia is usually expensive.

‘Encyclopedias are usually expensive.’

[Most x: ENCYCLOPEDIA(x)] EXPENSIVE(x)

c. A patient with this disorder seldom recovers.

‘Patients with this disorder seldom recover.’

[Few x: PATIENT(x)] RECOVER(x)

Further Exploration

Kearns ends by suggesting that singular indefinite NPs and bare plurals are analyzed as containing a free variable, while singular definite NPs refer to an individual. Krifka compares their behavior in predicates with kind reference, characterizing reference, and episodic reference.

1. Kind predicates

a. Potatoes were first cultivated in South America.

b. The potato was first cultivated in South America.

c. * A potato was first cultivated in South America.

2. Characterizing predicates

a. Potatoes contain vitamin C.

b. ? The potato contains vitamin C. (c.f. * The gentleman opens doors for ladies.)

c. A potato contains vitamin C.

3. Episodic predicates

a. Potatoes rolled out of the bag.

b. The potato rolled out of the bag.

c. A potato rolled out of the bag.

Kearns’ analysis should predict the behavior of the different types of NPs in each of these contexts. You should be able to provide an interpretation in predicate logic for each of these examples.

Krifka notes another context in which singular indefinite NPs and bare plurals display the same behavior.

4. Anaphor binding

a. John bought potatoes because they contain vitamin C.

b. John bought a potato because they contain vitamin C.

Rooth (1985), however, found anaphoric contexts in which singular indefinite Nps and bare plurals behave differently.

5. Rooth (1985)

a. At the meeting, Martians presented themselves as almost extinct.

b. * At the meeting, a Martian presented themselves/itself as almost extinct.

c. At the meeting, Martians claimed [PRO to be almost extinct].

d. * At the meeting, some Martians claimed [PRO to be almost extinct].

Carlson (1977) observed that singular indefinite NPs and bare plurals have different scopal behaviors. Bare plurals only allow interpretations with narrow scope.

6. Negation

a. A dog is here, and a dog is not here.

i. ∃x[DOG(x) & HERE(x)] & ∃x[DOG(x) & ~HERE(x)]

ii. ∃x[DOG(x) & HERE(x)] & ~∃x[DOG(x) & HERE(x)] (contradiction)

b. Dogs are here, and dogs are not here.

∃x[DOG(x) & HERE(x)] & ~∃x[DOG(x) & HERE(x)] (contradiction)

7. Propositional attitude verbs

a. Minnie wants to talk to a psychiatrist. (specific or non-specific)

b. Minnie wants to talk to psychiatrists. (only non-specific)

If we assume that bare plurals and singular indefinite NPs have a free variable interpretation, it is difficult to account for the following examples.

8. Hurricanes arise in this part of the Pacific. (Carlson 1989)

i. For hurricanes in general it holds: They arise in this part of the Pacific.

ii. For this part of the Pacific it holds: There are hurricanes that arise there.

9. A Frenchman wears a beret. (Krifka 2004)

i. For Frenchmen in general it holds: They wear berets.

ii. For berets in general it holds: They are worn by Frenchman.

Krifka finds that prosody can distinguish between these readings. Accent on the object results in reading (i), while accent on the subject results in reading (ii). He suggests making adverbial quantification sensitive to focus or to giveness presuppositions expressed by deaccenting.

The Boundaries of Word Meanings

Labov (1973) explored the meaning of the word cup by examining how its semantic extensions contrast with those of the words bowl, mug and vase. Labov employed a test proposed by Weinreich to see which of these ten conditions are criterial. Using the frame It’s an L but C establishes whether the condition C is an essential property of the object L. Thus, the oddity of the sentence It’s a chair but you can sit in it is due to the expectation that chairs are normally used for sitting. Labov provides the following results for the cup features:

It’s a cup but ...

a. *it’s concrete. it’s abstract.

b. *it’s inanimate. it’s alive.

c. *it’s concave. it’s convex.

d. *it holds things. it doesn’t hold things.

e. *it has a handle. it doesn’t have a handle.

f. *it’s pottery. it’s made of wax.

g. *it’s on a saucer. it has no saucer.

h. *it’s used at meal times. they use it to store things.

i. *you can drink out of it. you can eat out of it.

j. ?you can drink hot milk ?you can drink cold milk out

out of it. of it.

k. ?it has a stripe on it. ?it doesn’t have a stripe on it.

Labov finds many shortcomings in the typical dictionary definition of cup:

cup, n. 1. A small open bowl-shaped vessel used chiefly to drink from, with or without a handle or handles, a stem and foot, or a lid; as a wine cup, a Communion cup; specif., a handled vessel of china, earthenware, or the like commonly set on a saucer and used for hot liquid foods such as tea, coffee, or soup. (Webster’s New International Dictionary, 2nd edition).

This definition contains the qualifiers chiefly, commonly, or the like, etc. that hardly seem appropriate for a discrete category of objects. Labov comments that the description with or without a handle or handles can be applied to any object in the universe.

Labov points out that the word has extended uses that dictionaries often capture in additional entries. The sixth entry for cup covers the extended and metaphorical uses of cup:

6. A thing resembling a cup (sense 1) in shape or use, or likened to such a utensil; as (a) a socket or recess in which something turns, as the hip bone, the recess which a capstan spindle turns, etc. (b) any small cavity in the surface of the ground. (c) an annular trough, filled with water, at the face of each section of a telescopic gas holder, into which fits the grip of the section next outside. (d) in turpentine orcharding, a receptacle shaped like a flowerpot, metal or earthenware, attached to the tree to collect resin.

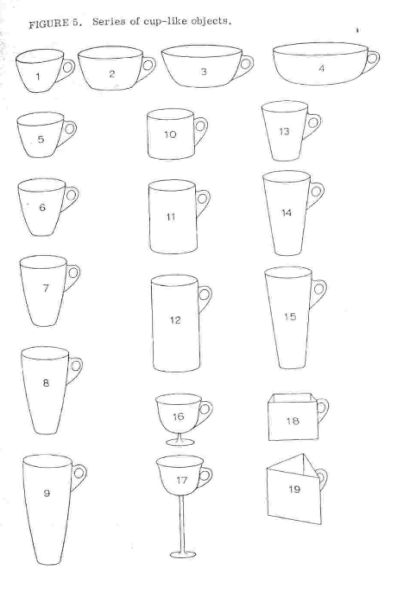

Labov designed a series of experiments to measure the vagueness of words like cup. He relied upon the analysis of vagueness by Max Black (1949). Black constructed a consistency profile that recognizes three dimensions: 1. the users of the language; 2. the situation in which the user is trying to apply the word L to an entity x; and 3. the consistency of application of L to x. Labov set out to determine how consistently a group of speakers would apply the word cup to a range of cup like drawings:

|

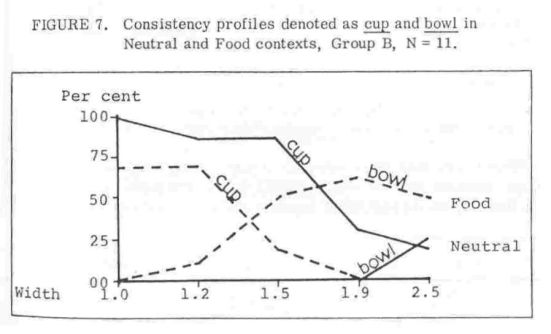

Labov first presented these drawings to subjects on at a time, and asked the subjects to name them. He then presented the drawings a second time and asked the subjects to imagine that they saw someone with the object in hand, stirring in sugar, and drinking coffee from it. In a third experiment, Labov presented the drawings, and asked subjects to imagine coming to dinner at someone’s house and seeing the object on the dinner table filled with rice. In a fourth experiment, the subjects were asked to think of the objects filled with cut flowers. Labov labels these four contexts as the ‘Neutral’, ‘Coffee’, ‘Food’ and ‘Flower’ contexts. The following chart displays the results for the Neutral and Food contexts.

|

|

In the Neutral context, the crossover point at which subjects begin to label the object a bowl rather than a cup occurs between cups 3 and 4. This point shifts to boundary between cups 2 and 3 in the Food context. Labov reports that the number of subjects labeling the item a cup was regularly elevated for the Coffee context, depressed by the Food context, and further depressed by the Flower context. These findings suggest that the functional context plays an enormous role in object labeling.

Labov concludes that form interacts with function in the process of denotation, and that the relation can be mapped through experimental methods of this sort.

Exercises

1. Write a description of your intuitions about the boundaries of the denotation of the word cup. Follow Labov’s procedures that I outlined in class to determine which factors affect your judgement about the denotation of cup. It will help to think of which factors are important for distinguishing cups from mugs, glasses, bowls, vases, etc. You should consult a dictionary for further leads. A significant part of this assignment will be to figure out a way of displaying your results in a graph or chart. Your graph should indicate how the factors you identify interact in determining the boundaries of the word. Be sure to include a discussion of your results and an explanation of how your graph captures (or fails to capture) these results. A further thought to ponder is the extent to which each of the defining factors you identify are themselves subject to contextual variation.

2. In the sentences below, all the predicates are habitual, therefore enduring. How are the existential and generic readings for bare plurals fixed in these sentences?

a. Beavers build dams.

b. dams are built by beavers.

c. Toxic liquids are produced in landfills.

d. Landfills produce toxic liquids.

3. The bare plurals in the following sentences seem to be in exactly similar contexts. Do they have the same kind of interpretation?

a. Shoes must be worn.

b. Dogs must be carried.

4. Translate the sentences in (3) into predicate logic expressions. Treat the passive predicates as 1-place predicates BE WORN and BE CARRIED.

References

Black, Max. 1949. Language and Philosophy. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Carlson, Greg N. 1977. Reference to kinds in English. Doctoral dissertation, University of Massachusetts. Also 1978, Indiana University Linguistics Club.

Carlson, Greg N. 1989. On the semantic composition of English generic sentences. In G. Chierchia, B. Partee and R. Turner (eds.), Properties, Types and Meaning. Volume 2: Semantic Issues, pp. 167-192. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Gould, Stephen Jay. 1995. Dinosaur in a Haystack. New York: Harmony Books.

Heim, I. 1982. The Semantics of Definite and Indefinite Noun Phrases. Doctoral dissertation, University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

Krifka, Manfred. 2004. Bare NPs: Kind-referring, indefinites, both or neither? Proceedings of Semantics and Linguistic Theory (SALT) XIII, University of Washington, Seattle. Edited R. B. Young & Y. Zhou, CLC Publications, Cornell.

Kripke, Saul. 1972. Naming and Necessity. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Labov, W. 1973. The boundaries of words and their meanings. In R. W. Fasold (ed.), Variation in the Form and Use of Language: A Sociolinguistic Reader, pp. 29-62. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press.

Petroski, Henry. 1990. The Pencil: A History of Design and Circumstance. New York: Knopf.

Petroski, Henry. 1993. The Evolution of Useful Things. New York: Knopf.

Pye, David. 1978. The Nature and Aesthetics of Design. London: Barrie & Jenkins.

Weinreich, U. 1962. Lexicographic definition in descriptive semantics. Problems in Lexicography 28(4) April.