|

|

6.4 Bare Plural NPs

Bare plural NPs are plural NPs that lack a determiner. People, cars, ideas, and fallacies are examples of bare plurals. Bare plurals behave differently from the other types of NPs we have analyzed. Bare plurals combine with predicates to produce existential and generic readings. Predicates denoting a temporary property produce an existential reading with bare plurals. Predicates that denote a lasting property produce a generic reading:

33. Existential reading

a. Firemen are available.

b. Teachers are patrolling the halls.

Generic reading

e. Firemen are altruistic.

f. Teachers are white-collar workers.

Kearns translates these readings into logic as:

35a. [∃x: FIREMAN(x)] AVAILABLE(x)

b. [∃x: TEACHER(x)] PATROLLING(x)

e. [Gen x: FIREMAN(x)] ALTRUISTIC(x)

f. [Gen x: TEACHER(x)] WHITE-COLLAR(x)

Gen represents generic quantification. Kearns’ generic treatment is a bit peculiar in that it literally translates as “generic firemen are altruistic”. Krifka (2004) suggests something like the following:

GEN ALTRUISTIC(FIREMEN)

Here, the generic quantifier can be interpreted as applying to possible worlds rather than individuals, i.e. GEN(w). The main question that Kearns is raising is whether bare plurals have a unique feature that interacts in different ways with different types of predicates.

Singular NPs can also have generic readings:

36a. Lilies are true bulbs.

b. The lily is a true bulb.

c. A lily is a true bulb.

Kearns suggests two approaches to accounting for the existential and generic readings for bare plurals found in (35). The first approach assumes that bare plurals incorporate an existential quantifier into the NP. This approach equates the sentence Firemen are available with the sentence Some firemen are available. Saying that bare plurals in such sentences contain existential quantification as part of the meaning of the NP is purely stipulative without independent evidence. Such an analysis fails to account for the difference between singular and plural NPs.

Another approach assumes that bare plurals contain a free variable that reacts to predicates in different ways. Active predicates contribute an existential quantifier while stative predicates contribute the generic operator. Kearns looks to quantificational adverbs for evidence in favor of one or another of these approaches. At this point, she does not examine whether bare plurals are different from definite and indefinite singular NPs in this respect.

There is a problem though. Kearns only examines bare plurals with stative predicates. What happens when we use bare plurals with non-stative predicates, e.g. Dogs are playing in the yard?

6.4.2 Bare Plurals and Quantificational Adverbs

Quantificational adverbs quantify over the times of an event:

37. Liam never / seldom / occasionally / sometimes / often / usually / always has breakfast.

These quantified times can be related to quantified Nps:

38. Adverb Quantified NP

never no mornings

seldom few mornings

occasionally a few mornings

sometimes some mornings

often many mornings

usually most mornings

always all mornings

Quantificational adverbs also seem to bind variables introduced by bare plurals. The following sentences show an ambiguity between a bound time reading and a bound variable reading:

39a. Dogs are often noisy.

Bound time: Dogs in general are noisy on many occasions.

Bound variable: [Many x: DOG(x)] NOISY(x) ‘Many dogs are noisy.’

b. Encyclopedias are usually expensive.

Bound time: Encyclopedias in general are expensive most of the time.

Bound variable: [Most x: ENCYCLOPEDIA(x)] EXPENSIVE(x) ‘Most encyclopedias are expensive.

c. Patients with this disorder seldom recover.

Bound time: Patients with this disorder in general recover on few occasions.

Bound variable: [Few x: PATIENT(x)] RECOVER(x) ‘Few patients with this disorder recover.

This evidence supports the second analysis of bare plurals incorporating a free variable rather

than the first approach in which the bare plural contains an existential quantifier. The free variable analysis predicts that bare plurals will induce distributive readings in which the predicate applies separately to each individual rather than to the group or sum individual.

6.5 Generic NPs and Reference to Kinds

Kearns returns to the puzzle created by the generic reference by different types of NPs:

42a. Lilies are true bulbs.

b. A lily is a true bulb.

c. The lily ia a true bulb.

Reference to natural kinds produces one type of generic reference. A natural kind is a natural category of thing or substance. Mass substances such as gold and water, as well as animal and plant species such as tigers and lilies are natural kinds. Natural kinds may be referred to by scientific terms or by their common name:

43a. Canis familiaris is a popular pet.

c. The dog is a popular pet.

There are a few predicates that are closely associated with a natural kind as a group. Krifka (2004) labels these kind reference.

44a. The dodo is extinct.

b. The panda may die out.

Other predicates used with natural kinds apply to individual members of the group. Krifka labels these characterizing statements.

45a. The African grey parrot has a strong curved beak.

b. The kiwi lays enormous eggs.

This is similar to the ambiguity with nouns like paper that refer to either the object or the substance. Kearns then examines whether the singular definite NPs in (45) have the same interpretation as the bare plurals she discussed in the previous section. If so, they should display the same distributive interpretations as the bare plurals. Kearns discusses several arguments against a distributive (free variable) interpretation and in favor of an abstract kind individual interpretation of the singular definite NPs in (45).

1. The predicates in (45) can be given a kind interpretation by taking the properties of the individuals that make up the kind to define a kind individual, which acts as a substitute for reference to the group. We expect each member of the kind to display the characteristic properties of the group. This accounts for the distributive reading of the sentences in (45). A single abstract African grey parrot can stand in for the group.

2. Applying distributive predication to the members of a kind does not explain why characterizing statement can apply to some members of the group rather than to all of the members. Sentences like The hedgehog is affected by ringworm show that a tendency to display a given feature is sufficient to characterize the entire group, even though it is impossible to say what proportion of hedgehogs suffer from ringworm. This difficulty is avoided by attributing the property directly to the kind through a kind individual rather than to its individual members.

3. Generic NPs such as the teacher cannot be used in distributive (characterizing) contexts that are acceptable with bare plurals (51), singular collectives (52) and reciprocals like each other (53).

50a. Lions gather at the water-hole in the evening.

e. * The lion gathers at the water-hole in the evening.

51c. The family gathers for meals.

d. The family gather for meals.

52a. The family support each other.

b. Teachers support each other.

c. * The teacher support each other.

d. * The teacher supports each other.

These differences can be explained by assuming that singular definite NPs refer to some kind of individual rather than an expression with a free variable.

4. Bare plurals also contrast with generic singular definites in cumulative predication:

53a. Bulls have horns.

b. Unicorns have horns.

c. The bull has horns.

d. The unicorn has horns.

(53d) implies that unicorns have more than one horn so it is false. The unicorn in (53d) cannot be given a cumulative reading to allow the number of horns to increase with each additional member of the group, so the only option is the reading where a single unicorn has more than one horn.

5. Definite singular NPs sound odd if used generically for groups of objects that don’t constitute natural kinds:

54a. The Coke bottle has a narrow neck. (specific and generic)

b. A Coke bottle has a narrow neck.

c. Coke bottles have narrow necks.

d. * The green bottle has a narrow neck. (ok with specific interpretation)

e. A green bottle has a narrow neck.

f. Green bottles have narrow necks.

The generic interpretation of the definite singular NP in (54d) presupposes that a green bottle is a particular kind of bottle, which is not the case.

These arguments show that definite singular generic NPs denote an abstract single individual which has properties that are found on individual members of the kind. Indefinite singular generic NPs and bare plurals allow generalizations about individuals who fit a given description, even though they may not form a natural kind.

Indefinite singular NPs, like bare plurals, have existential readings with predicates denoting temporary properties, and generic readings with predicates denoting enduring properties:

56. Existential reading

a. A fireman is available.

b. A teacher is on duty

Generic reading

d. A fireman is altruistic.

e. A teacher is a white-collar worker.

Heim (1982) proposed treating singular indefinite NPs may be treated like bare plurals and bound by a quantifier in another part of the sentence. Kearns provides the following examples:

57a. A dog is often noisy.

‘Dogs are often noisy.’

[Many x: DOG(x)] NOISY(x)

b. An encyclopedia is usually expensive.

‘Encyclopedias are usually expensive.’

[Most x: ENCYCLOPEDIA(x)] EXPENSIVE(x)

c. A patient with this disorder seldom recovers.

‘Patients with this disorder seldom recover.’

[Few x: PATIENT(x)] RECOVER(x)

Further Exploration

Kearns ends by suggesting that singular indefinite NPs and bare plurals are analyzed as containing a free variable, while singular definite NPs refer to an individual. Krifka compares their behavior in predicates with kind reference, characterizing reference, and episodic reference.

1. Kind predicates

a. Potatoes were first cultivated in South America.

b. The potato was first cultivated in South America.

c. * A potato was first cultivated in South America.

2. Characterizing predicates

a. Potatoes contain vitamin C.

b. ? The potato contains vitamin C. (c.f. * The gentleman opens doors for ladies.)

c. A potato contains vitamin C.

3. Episodic predicates

a. Potatoes rolled out of the bag.

b. The potato rolled out of the bag.

c. A potato rolled out of the bag.

Kearns’ analysis should predict the behavior of the different types of NPs in each of these contexts. You should be able to provide an interpretation in predicate logic for each of these examples.

Krifka notes another context in which singular indefinite NPs and bare plurals display the same behavior.

4. Anaphor binding

a. John bought potatoes because they contain vitamin C.

b. John bought a potato because they contain vitamin C.

Rooth (1985), however, found anaphoric contexts in which singular indefinite Nps and bare plurals behave differently.

5. Rooth (1985)

a. At the meeting, Martians presented themselves as almost extinct.

b. * At the meeting, a Martian presented themselves/itself as almost extinct.

c. At the meeting, Martians claimed [PRO to be almost extinct].

d. * At the meeting, some Martians claimed [PRO to be almost extinct].

Carlson (1977) observed that singular indefinite NPs and bare plurals have different scopal behaviors. Bare plurals only allow interpretations with narrow scope.

6. Negation

a. A dog is here, and a dog is not here.

i. ∃x[DOG(x) & HERE(x)] & ∃x[DOG(x) & ~HERE(x)]

ii. ∃x[DOG(x) & HERE(x)] & ~∃x[DOG(x) & HERE(x)] (contradiction)

b. Dogs are here, and dogs are not here.

∃x[DOG(x) & HERE(x)] & ~∃x[DOG(x) & HERE(x)] (contradiction)

7. Propositional attitude verbs

a. Minnie wants to talk to a psychiatrist. (specific or non-specific)

b. Minnie wants to talk to psychiatrists. (only non-specific)

If we assume that bare plurals and singular indefinite NPs have a free variable interpretation, it is difficult to account for the following examples.

8. Hurricanes arise in this part of the Pacific. (Carlson 1989)

i. For hurricanes in general it holds: They arise in this part of the Pacific.

ii. For this part of the Pacific it holds: There are hurricanes that arise there.

9. A Frenchman wears a beret. (Krifka 2004)

i. For Frenchmen in general it holds: They wear berets.

ii. For berets in general it holds: They are worn by Frenchman.

Krifka finds that prosody can distinguish between these readings. Accent on the object results in reading (i), while accent on the subject results in reading (ii). He suggests making adverbial quantification sensitive to focus or to giveness presuppositions expressed by deaccenting.

Noun Classes

The distinction between count and mass nouns reflects the structure of quantified expressions in any given language. English requires the use of a plural on nouns that refer to humans, animals and objects, i.e., count nouns. A mass must be divided into countable units before it can be counted (e.g., a cup of, three heads of). In contrast, Japanese only uses a plural on human nouns, and the plural is optional. Japanese requires a numeral classifier to be used for all nouns—human, animal, object and substance. The crosslinguistic study of classifiers provides additional insights into the structure of nominal reference.

Grinevald (2003) identifies four types of classifier systems:

POSS+ CLASS Numeral+ CLASS CLASS+Noun // Verb- CLASS

Genitive Numeral Noun Verbal

Classifier Classifier Classifier Classifier

The following examples illustrate these different types.

Genitive Classifiers: Ponapean (Rehg 1981:184)

Kene-i mwenge Were-i pwoht

EDIBLE.CLASS-my food TRANSPORT.CLASS-my boat

‘my food’ ‘my boat’

Numeral Classifiers: Ponapean (Rehg 1981:130)

Pwihk riemen Tuhke rioapwoat

pig 2+ANIMATE.CLASS tree 2+LONG.CLASS

‘two pigs’ ‘two trees’

Noun Classifiers: Jakaltek (Craig 1986:264)

xil naj xuwan no7 lab’a

saw MAN.CLASS John ANIMAL.CLASS snake

‘John saw the snake.’

Verbal Classifiers: Cayuga (Mithun 1986:386-388)

Ohon’atatke: ak-hon’at-a:k So:wa:s akh-nahskw-ae’

It-potato-rotten past.I-POTATO.CLASS-eat Dog I-DOMESTIC.ANIMAL.CLASS-have

‘I ate a rotten potato.’ ‘I have a dog.’

Denny (1976:125) observed that nominal classifiers divide into three main semantic categories based on social, physical and functional interaction. Languages commonly distinguish animate entities, and especially humans in the social sphere, by gender and social rank. Interaction with physical objects leads to distinctions based on their physical properties, especially shape and material. Since the physical properties of objects are closely associated with their functional properties, it is a mistake to attribute a classifier’s use to one or the other. Many shape classifiers were historically derived from nominals in the vegetal domain (Adams 1986):

Shape Classifiers Lexical Origin

1D: long-rigid tree/trunk

2D: flat flexible leaf

3D: round fruit

Nominal classifiers can be divided into two further groups. Sortal classifiers distinguish between different categories or sorts of objects based on their shape, material or function. They include such distinctions as “round” oranges, “long rigid” arrows, and “flat, flexible” blankets. Mensural classifiers distinguish between different measures (“handful” of flour, “flock” of geese, “cup” of soda) and configurations (“pile” of books, “line” of geese, “puddle” of soda) of objects. Mensural classifiers often make up the bulk of numeral classifiers, whereas the number of sortal classifiers can be quite small.

Grinevald (2000) suggests that the locus of numeral classifiers shows a curious alignment with their meaning. Shape is the major semantic parameter among numeral classifiers, function is the main semantic parameter for genitive classifiers, and material is the dominant semantic parameter for noun classifiers.

Languages use classifiers to identify and track referents in discourse; their classificatory function is secondary to their discourse function. Thus, nominal classifiers should be properly grouped with restricted quantifiers in that nominal classifiers establish the identity of a referent by establishing a restricted set of individuals.

Ponapean

Pwihk riemen

pig 2+ANIMATE.CLASS

‘two pigs’

[2x: ANIMATE(x) & PIG(x)]

The Boundaries of Word Meanings

Labov (1973) explored the meaning of the word cup by examining how its semantic extensions contrast with those of the words bowl, mug and vase. He noted that the ‘categorical view’ of word meaning assumes that categories are:

1. discrete

2. invariant

3. qualitatively distinct

4. conjunctively defined

5. composed of atomic primes

Labov provides the following diagrams to illustrate the difference between the presence and absence of a categorical boundary.

|

Item a b c d e f g h P 1 + + + + - - - - r 2 + + + + - - - - o 3 + + + + - - - - p 4 + + + + - - - - e 5 + + + + - - - - r 6 + + + + - - - - t 7 + + + + - - - - y X ←CATEGORY→ Y |

Item a b c d e f g h P 1 + + + + + + + - r 2 + + + + + + - - o 3 + + + + + - - - p 4 + + + + - - - - e 5 + + + - - - - - r 6 + + - - - - - - t 7 + - - - - - - - y X ←CATEGORY→ Y |

He analyzed the semantic features in the following definition for the word cup:

2. The term cup is used for an object which is (a) concrete and (b) inanimate and (c) upwardly concave and (d) a container (e) with a handle (f) made of earthenware or other vitreous material and (g) set on a saucer and (h) used for the consumption of food (I) which is liquid [(j) and hot] ... (37)

Labov employed a test proposed by Weinreich to see which of these ten conditions are criterial. Using the frame It’s an L but C establishes whether the condition C is an essential property of the object L. Thus, the oddity of the sentence It’s a chair but you can sit in it is due to the expectation that chairs are normally used for sitting. Labov provides the following results for the cup features:

It’s a cup but ...

a. *it’s concrete. it’s abstract.

b. *it’s inanimate. it’s alive.

c. *it’s concave. it’s convex.

d. *it holds things. it doesn’t hold things.

e. *it has a handle. it doesn’t have a handle.

f. *it’s pottery. it’s made of wax.

g. *it’s on a saucer. it has no saucer.

h. *it’s used at meal times. they use it to store things.

i. *you can drink out of it. you can eat out of it.

j. ?you can drink hot milk ?you can drink cold milk out

out of it. of it.

k. ?it has a stripe on it. ?it doesn’t have a stripe on it.

Labov finds many shortcomings in the typical dictionary definition of cup:

cup, n. 1. A small open bowl-shaped vessel used chiefly to drink from, with or without a handle or handles, a stem and foot, or a lid; as a wine cup, a Communion cup; specif., a handled vessel of china, earthenware, or the like commonly set on a saucer and used for hot liquid foods such as tea, coffee, or soup. (Webster’s New International Dictionary, 2nd edition).

This definition contains the qualifiers chiefly, commonly, or the like, etc. that hardly seem appropriate for a discrete category of objects. Labov comments that the description with or without a handle or handles can be applied to any object in the universe.

Labov points out that the word has extended uses that dictionaries often capture in additional entries. The sixth entry for cup covers the extended and metaphorical uses of cup:

6. A thing resembling a cup (sense 1) in shape or use, or likened to such a utensil; as (a) a socket or recess in which something turns, as the hip bone, the recess which a capstan spindle turns, etc. (b) any small cavity in the surface of the ground. (c) an annular trough, filled with water, at the face of each section of a telescopic gas holder, into which fits the grip of the section next outside. (d) in turpentine orcharding, a receptacle shaped like a flowerpot, metal or earthenware, attached to the tree to collect resin.

Labov designed a series of experiments to measure the vagueness of words like cup. He relied upon the analysis of vagueness by Max Black (1949). Black constructed a consistency profile that recognizes three dimensions: 1. the users of the language; 2. the situation in which the user is trying to apply the word L to an entity x; and 3. the consistency of application of L to x. Labov set out to determine how consistently a group of speakers would apply the word cup to a range of cup like drawings:

|

|

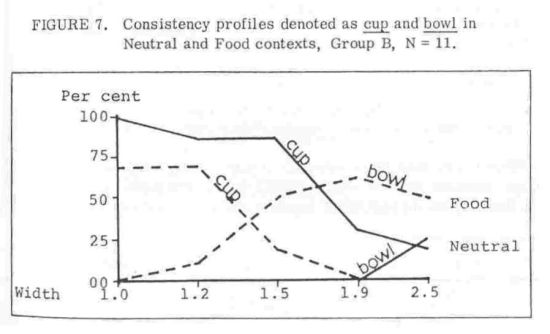

Labov first presented these drawings to subjects on at a time, and asked the subjects to name them. He then presented the drawings a second time and asked the subjects to imagine that they saw someone with the object in hand, stirring in sugar, and drinking coffee from it. In a third experiment, Labov presented the drawings, and asked subjects to imagine coming to dinner at someone’s house and seeing the object on the dinner table filled with rice. In a fourth experiment, the subjects were asked to think of the objects filled with cut flowers. Labov labels these four contexts as the ‘Neutral’, ‘Coffee’, ‘Food’ and ‘Flower’ contexts. The following chart displays the results for the Neutral and Food contexts.

|

|

In the Neutral context, the crossover point at which subjects begin to label the object a bowl rather than a cup occurs between cups 3 and 4. This point shifts to boundary between cups 2 and 3 in the Food context. Labov reports that the number of subjects labeling the item a cup was regularly elevated for the Coffee context, depressed by the Food context, and further depressed by the Flower context. These findings suggest that the functional context plays an enormous role in object labeling. The following chart shows more details.

|

|

Labov concludes that form interacts with function in the process of denotation, and that the relation can be mapped through experimental methods of this sort.

Exercises (Kearns p. 143-145)

1. The underlined NP in the following sentences can have either a specific or nonspecific interpretation. Give a logical translation for each sentence and indicate which is specific and which nonspecific.

a. Karen wants to shoot a lion.

b. Eric didn’t meet a reporter.

c. Clive might buy a painting.

d. Every flautist played a sonata.

2. In the sentences below, all the predicates are habitual, therefore enduring. How are the existential and generic readings for bare plurals fixed in these sentences?

a. Beavers build dams.

b. dams are built by beavers.

c. Toxic liquids are produced in landfills.

d. Landfills produce toxic liquids.

3. The bare plurals in the following sentences seem to be in exactly similar contexts. Do they have the same kind of interpretation?

a. Shoes must be worn.

b. Dogs must be carried.

4. Translate the sentences in (3) into predicate logic expressions. Treat the passive predicates as 1-place predicates BE WORN and BE CARRIED.

References

Adams, K. 1986. Numeral classifiers in Austroasiatic. In C. Craig (ed.), Noun Classes and Categorization, pp. 241-263. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Aikhenvald, A. Y. 2000. Classifiers: A Typology of Noun Classification Devices. New York: Oxford University Press.

Black, Max. 1949. Language and Philosophy. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Carlson, Greg N. 1977. Reference to kinds in English. Doctoral dissertation, University of Massachusetts. Also 1978, Indiana University Linguistics Club.

Carlson, Greg N. 1989. On the semantic composition of English generic sentences. In G. Chierchia, B. Partee and R. Turner (eds.), Properties, Types and Meaning. Volume 2: Semantic Issues, pp. 167-192. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Craig, C. G. 1986. Jacaltec noun classifiers: a study in language and culture. In C. Craig (ed.), Noun Classes and Categorization, pp. 263-293. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Craig, C. G. 1987. Jacaltec noun classifiers. A study in grammaticalization. Lingua 71:41-284.

Denny, J. P. 1976. What are noun classifiers good for? In S. Mufwene, S. Walker & S. Steever (eds.), Papers from the Twelfth Regional Meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society 12:122-132.

Grinevald, C. 2000. A morphosyntactic typology of classifiers. In G. Senft (ed.), Nominal Classification, pp. 50-92. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Grinevald, C. 2003. Classifier systems in the context of a typology of nominal classification. In K. Emmorey (ed.), Perspectives on Classifier Constructions in Sign Languages, pp. 91-110. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Heim, I. 1982. The Semantics of Definite and Indefinite Noun Phrases. Doctoral dissertation, University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

Krifka, Manfred. 2004. Bare NPs: Kind-referring, indefinites, both or neither? Proceedings of Semantics and Linguistic Theory (SALT) XIII, University of Washington, Seattle. Edited R. B. Young & Y. Zhou, CLC Publications, Cornell.

Labov, W. 1973. The boundaries of words and their meanings. In R. W. Fasold (ed.), Variation in the Form and Use of Language: A Sociolinguistic Reader, pp. 29-62. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press.

Mithun, M. 1986. The convergence of noun classification systems. In C. Craig (ed.), Noun Classes and Categorization, pp. 379-397. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Rehg, K. 1981. Ponapean Reference Grammar. PALI Language Texts: Micronesia. Honolulu: The University Press of Hawaii.

Rooth, Mats. 1985. Association with focus. Doctoral dissertation, University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

Weinreich, U. 1962. Lexicographic definition in descriptive semantics. Problems in Lexicography 28(4) April.