Semantic Development

Levels of meaning

1. Lexical semantics - word meaning (lexical contrast, synonyms, etc.)

2. Propositional semantics - sentence meaning

Thematic relations (agent, theme, etc.)

Scope relations, e.g., ‘All of the arrows didn’t hit the target’

(¬ ∀ arrows) hit (target) vs. (∀ arrows) ¬ hit (target)

3. Pragmatic additions

The linguistic context in the form of the surrounding discourse.

‘Jake broke the cup’

The situational context in the form of the physical situation of the utterance.

‘All of the students took the exam’

The social context provides cultural conventions for interpreting utterances.

‘My bad’

General issues

1. Semantic features vs. holism (Quine - Word and Object)

Semantic features similar to elements ‘the ultimate constituents of meaning’

E.g., bird {wings, feathers, beak, ...)

Holism - the meaning of each word depends on the meaning of other words

2. Perceptual features (Clark 1973) vs. Functional features (Nelson 1974)

Perceptual features: shape, smell, color, feel, sound; ball - [+ round]

Functional features: uses, actions; ball - s.t. to throw, bounce

3. Definitional (Fodor 1975) vs. Clusters (Wittgenstein 1953)

Definitional - necessary and invariant features; ball - [+ round]

Clusters - family resemblances (Rosch 1973); ‘game’, ball - prototypical features

4. Innate (Fodor 1975) vs. Learned (Anglin 1977)

Innate - universal and permanent features; ball - always [+ round]

Learned - language specific and adjustable; ball - this particular ball

Criticisms of feature theories

1. features are arbitrary (Burling AA 1964 ‘God’s truth or hocus pocus?’)

Man: [+ male] or [- female]

number: ‘cut’ in number line (Dedikine) or a set (Russell & White)

water: [+ H2O] on earth, [+ XYZ] on twin earth (Putnam 1975)

2. features aren’t sufficient (Lyons 1973)

Blue: [+ color, + blue?]

3. features are incompatible with semantic change

Newton’s ‘Momentum’ = mass x velocity before Einstein (Putnam 1996)

ball with [+ round] doesn’t allow for kush balls

OE mete ‘food’ –> meat; OE foda ‘fodder’ –> food

forks weren’t common before 1800 (Petrosky 1996)–used to refer to pitchforks

1554 ‘I give and bequeath my neighbor ... my spone with a forke in the end’ (a spork!)

4. feature theories are a type of referential semantic theory

The meaning of a feature is tied to its reference, e.g., [+ round]

reference is inadequate: ‘morning star’ vs. ‘evening star’ (Frege)

If features aren’t referential, what are they?

If features are something else, concepts?, then they aren’t explanatory constructs.

Cross-Linguistic Differences

Melissa Bowerman pioneered the cross-linguistic study of topological encoding. She initially looked at the encoding of in and on in English, Berber, Dutch and Spanish.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I. Nyoman Aryawibawa (2008) explored the semantics of spatial relations in Rongga, Balinese, and Indonesian. These languages employ unmarked prepositions to express normal relations between objects and marked prepositions to express abnormal relations.

|

|

|

|

Rongga

|

Kain meja one meja |

Li’e munde one mok |

|

cloth table on table |

that orange in bowl |

|

‘The table cloth is on the table’ |

‘The orange is in the bowl’ |

Changing to an abnormal relation between the figure and ground results in the use of a marked preposition. The marked form is used if the table cloth is folded and then put back on the table or if a ribbon is put in the bowl instead of an orange.

|

Kain meja zheta wewo meja |

Pita zhale one mok |

|

cloth table on table |

ribbon in bowl |

|

‘The table cloth is on the table’ |

‘The ribbon is in the bowl’ |

Theories of semantic development

1. Semantic Feature Hypothesis (Eve Clark 1973)

a. children begin with superordinate features and learn subordinate features

[ANIMATE] –> [ANIMATE, CANINE]

b. predicts early overextensions based on perceptually salient features, e.g., movement, shape, size

antonyms like ‘same’ vs. ‘different’ and ‘more’ vs. ‘less’ are first acquired with similar meanings

Children first acquire ‘unmarked’ features, e.g. ‘big’ vs. ‘little’

2. Functional Core Concept theory (Katherine Nelson 1974)

a. children begin with a concept that is not purely perceptual, and attach a word to it

b. follow four steps (Table 8.13, p. 400)

1. identify the object, e.g., ball

2. recognize context-bound functional features, e.g., throw, roll, bounce

3. identify core ‘invariant’ functions, e.g., roll, bounce

4. acquire word

c. predicts words acquired early would be underextended

d. Nelson does not state how the theory can be extended to adjectives or verbs

Both theories assume a definitional approach to word meaning

Both theories treat word meanings in isolation from other words

3. Prototype theory (Eleanor Rosch; Anglin 1977, Bowerman 1978a)

a. definitions of key terms (Anglin 1977:27)

1. Term of reference ‘a word. . . which denotes or refers to real objects’

2. Extension: ‘all the objects which an individual is willing to denote’ with a term of reference

3. Intension: ‘the set of properties which an individual believes to be true of the instances of the category denoted’ by a term of reference

4. Concept: ‘all of the knowledge possessed by an individual about the category of objects denoted’ by a term of reference. ‘This knowledge includes both knowledge of extension and knowledge of intension.’

b. acquisition

1. child forms a perceptual schema of an object analogous to a prototype

the schema begins at an intermediate semantic level;

it also includes core functional features

the child’s extensional knowledge is not well coordinated with it intensional knowledge

Children’s word overextensions are based on perception

Their word definitions (intensions) are primarily functional, e.g. ‘apple’ st eaten

2. school-aged children learn to coordinate their lexical knowledge into hierarchical systems

Acquisition Studies

1. Anglin (1977) noun acquisition Study 1

a. order of acquisition–superordinate, intermediate, subordinate

Brown (1958b): children start with intermediate level, e.g., ‘money’, not ‘thing’ or ‘dime’

b. problem: child could use an intermediate adult word as a superordinate or subordinate term

c. Anglin’s stimuli:

|

Level |

I |

II |

III |

|

Superordinate |

animal |

plant |

food |

|

Intermediate |

dog |

flower |

fruit |

|

Subordinate |

collie |

rose |

apple |

He used 4 sets of 3 pictures rated by adults for each word

3 ‘prototypical’ animals: King Charles spaniel, African elephant, cat

3 ‘peripheral’ animals: bullfrog, monarch butterfly, marsh hawk

20 children between 2 and 5 years old participated

The children were asked to name each picture in the set and then asked ‘What are all these?’

d. Results (Table 8.14, p. 407)

Child

|

Adult |

percent correct |

most common response |

|

animals |

50 |

animals |

|

dogs |

100 |

dogs |

|

collies |

0 |

dogs |

|

|

|

|

|

plants |

15 |

flowers |

|

flowers |

70 |

flowers |

|

roses |

10 |

flowers |

|

|

|

|

|

foods |

40 |

foods |

|

fruits |

20 |

foods |

|

apples |

95 |

apples |

‘There is neither a unidirectional specific-to-general progression in vocabulary development nor a unidirectional general-to-specific progression.’ (67)

e. factors governing semantic development

1. relevance–is the word important to the child

2. function–groupings that are useful to the child

3. frequency–how often does the child hear the word

2. Study 2 extension

a. Anglin’s stimuli:

|

Level |

I |

II |

III |

|

Superordinate |

animal |

food |

plant |

|

Intermediate |

dog |

fruit |

flowerr |

|

Subordinate |

collie |

apple |

tulip |

b. participants

18 children with ages 2;6 to 4;0

18 children aged 4;6 to 6;0

18 adults

c. each asked ‘Is this a (e.g.) fruit?’ when shown instances and non-instances

d. Results

1. children showed both overextensions and underextensions (most frequent)

|

|

underextensions |

overextensions |

|

18 children aged 2;6 to 4;0 |

29% |

8% |

|

18 children aged 4;6 to 6;0 |

16% |

6% |

2. Denied woman was an animal and praying mantis and caterpillar were animals

e. Explanation

1. individual variation

2. the specific concept

Flower overextended to elephant ear, coconut, and a philodendron

Plant was usually underextended; rejected trees as examplars of plants

3. the stimuli

Peripheral examplars were less likely to be correctly identified

3. Study 3 intension

a. 14 children between 2;8 and 6;7

b. each asked to discuss the meaning of 12 words: dog, food, flower, vehicle, animal, apple,

rose, car, collie, fruit, plant, and Volkswagon

What is a ____?

Tell me everything you can about ______.

What kinds of _______s are there?

What kind of thing is a _____?

Tell me a story about a _____.

c. children were not able to give a set of defining properties for a word’s meaning

e.g., Peter (2;8) for ‘dog’, ‘it goes woof, barks’–instance oriented

Bowerman (1978a)

a. diary study of her two daughters, Eva and Christy

b. findings (Table 8.15, p. 410)

|

|

Eva |

Christy |

|

1. Overextensions based on perceptual similarities |

moon |

snow |

|

|

|

money |

|

2. Words extended on the basis of subjective experience |

there! |

aha! |

|

|

heavy |

heavy |

|

|

too tight |

|

|

3. Words used noncomplexively for referents with shared attributes |

ball |

on-off |

|

|

ice |

|

|

|

off |

|

|

4. Complexively used words with prototypical referents |

kick |

night-night |

|

|

open |

open |

|

|

close |

|

|

|

giddiup |

|

|

|

moon |

|

Eva ‘moon’ used for ball of spinach, hangnails, the letter D

Overextensions of non-nominals based on child’s subjective experiences

There! Experience of completing a project

c. both complexive and noncomplexive overextensions occur from the beginning

d. complexive use was somewhat more frequent for action words than for object words

e. the girls assigned different meanings to the same words, e.g.,

Christy ‘on-off’: ‘any act involving the separation or coming together of two objects’ (p. 271), e.g., getting socks on or off; getting off a spring-horse; taking pop-beads on and off; separating stacked cups; putting phone on hook; etc.

Eva ‘off’: ‘removal of clothes and other objects from the body’ (p. 271), e.g. for shoes, car safety harness, glasses, pacifier, bib, diaper, etc.

f. the complexive examples suggest an underlying organization around a prototype

|

Word |

Prototype |

Features |

|

kick |

kicking a ball with the foot so |

a. waving limb |

|

|

that it is propelled forward |

b. sudden sharp contact |

|

|

|

c. object propelled |

|

night-night |

person or doll lying down in |

a. crib, bed |

|

|

bed or crib |

b. blanket |

|

|

|

c. non-normal horizontal position |

|

close |

closing drawers, doors, boxes, |

a. bringing together two objects or parts |

|

|

jars, etc. |

b. cause something to be concealed |

|

open |

opening drawers, doors, boxes, |

a. separation of parts which were in contact |

|

|

jars, etc. |

b. cause something to be revealed |

|

giddiup |

bouncing on a spring horse |

a. horse |

|

|

|

b. bouncing motion |

|

|

|

c. sitting on toy |

|

moon |

the real moon |

a. circular shape |

|

|

|

b. yellow color |

|

|

|

c. shiny surface |

|

|

|

d. viewing position |

|

|

|

e. flatness |

|

|

|

f. broad expanse |

Eva used the word ‘kick’ on seeing a picture of a kitten with a ball near its paw; watching cartoon turtles on TV doing the can-can; pushing her stomach against a mirror.

g. Bowerman concludes (p. 278) ‘These findings suggest that there is less discontinuity between child and adult methods of classification than has often been supposed.’ She does not explain how her daughters acquire adult extensions.

Solving Quine’s Problem (Word & Object 1960)

‘radical translation’–does ‘gavagai’ refer to the whole object, the collection of undetached parts, or a stage?

1. Hypothesis testing (induction) can lead to radically different interpretations

2. Solution–universal constraints that predispose children to the proper adult extensions

a. Whole object bias (Markman 1994; also Golinkoff, Mervis & Hirsh-Pasek 1994 JCL)

A novel label is likely to refer to the whole object and not to its parts, substance, or other properties.

b. Taxonomic bias

Labels refer to objects of the same kind rather than to objects that are thematically related.

c. Mutual exclusivity bias (Also Clark 1987, The Principle of Contrast)

Words are mutually exclusive.... Each object will have one and only one label.

3. Problems

a. The proposed constraints cannot be extended to other lexical categories, e.g., verbs

b. The constraints are vague

i. the specific object or objects of the same kind

ii. ‘the same kind’

c. The constraints are false (Gathercole 1989 JCL, e.g., couch/sofa; -s/-z)

Recent Studies

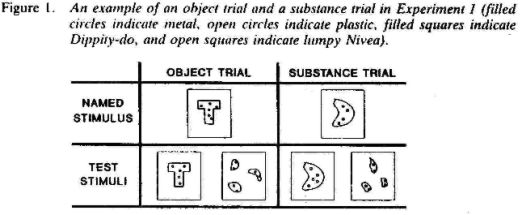

Soja, Carey & Spelke (1991 Cognition 38.178-211 ‘Ontological categories guide young children’s inductions of word meaning)

a. Examined children’s understanding of the distinction between some sand and some dog. Is the distinction between objects and substances innate?

b. Subjects: 24 two-year-olds (x = 2;1)

|

c. Conditions: |

Neutral syntax |

Informative syntax |

|

|

‘This is my blicket’ |

‘This is a blicket’ |

|

|

‘Point to the stad’ |

‘This is more stad’ |

|

|

d. Stimuli: novel objects and substances, e.g., apple corers, plumbing fixtures; coffee

e. Results: percent object responses

|

|

Neutral |

Informative (chance = 50%) |

|

Objects |

93% |

94% |

|

Substances |

24% |

38% |

f. Conclusion:

i. Children can distinguish between objects and substances by two years of age

They generalize by shape when the referent is an object

They generalize by texture when the referent is a substance

ii. Children do not rely upon linguistic cues to make the distinction between objects and substances

Imai & Gentner (1997 Cognition 62.169-200 ‘A cross-linguistic study of early word meaning: universal ontology and linguistic influence’)

a. Subjects: American and Japanese

14 children at 2;1; 15 children at 2;8; 14 children at 4;2; 18 adults

|

|

humans |

animals |

objects |

stuff |

|

|

|

|

|

requires classifier, e.g. ‘a cup of ...’ |

|

English |

obligatory plural |

no plural |

||

|

Japanese |

optional |

no plural |

|

|

|

|

requires classifier (unitizer) |

|

|

|

b. Stimuli

|

|

Standard |

Shape Alternative |

Material Alternative |

|

Complex Object |

plastic clip |

metal clip |

plastic piece |

|

Simple Object |

cork pyramid |

plastic pyramid |

cork piece |

|

Substance |

sawdust |

leather pieces |

two sawdust piles |

c. Results: percent object responses

|

|

Early 2 |

Late 2 |

Adult |

|||

|

|

Am |

Jp |

Am |

Jp |

Am |

Jp |

|

Complex Objects |

82% |

79% |

88% |

94% |

94% |

90% |

|

Simple Objects |

68% |

50% |

75% |

53% |

75% |

36% |

|

Substances |

34% |

45% |

55% |

20% |

51% |

15% |

d. Conclusions:

i. Both American and Japanese subjects distinguish between objects and substances

ii. American subjects had a higher proportion of shape responses in simple object and substance trials

iii. Japanese children showed no bias for simple object trials; American adults have an object bias; Japanese adults have a substance bias

iv. Japanese subjects show a clear substance bias for substance trials

v. All children make a distinction between objects and substances, but language influences where the division is made

Landau, Leyton, Lynch & Moore (PRCLD 1992)

a. Subjects: 3;0

b. Stimuli

|

This is a dax. |

Is this a dax? |

||

|

|

|

|

|

c. Conclusion: Children’s attention to object shape is subject to their theory about the object

Verb Meaning (Choi & Bowerman, 1991 Cognition ‘Learning to express motion events in English and Korean’)

Talmy (1985) observed that languages may be divided into:

Satellite-framed languages (e.g., English) Verb-framed languages (e.g., Spanish)

The bottle floated into the cave La botella entró a la cuevaflotando

Figure Motion+Manner Path Figure Motion+PathManner

Korean verbs also conflate motion and path

|

kkita/ppayta |

put on/take off |

(tight fit, e.g., Legos, pen top, ring on finger) |

|

nehta/kkenayta |

put in/take out |

(loose fit, e.g., furniture in room) |

|

tamta/kkenayta |

put in/take out |

(multiple objects, e.g., fruit in basket) |

|

ipta |

put on clothes |

|

ssuta |

put on hats |

|

sinta |

put on socks/shoes |

a. Subjects: Choi visited 4 Korean children (14-34 months old) every 3-4 weeks; compared with Bowerman’s diary study of 2 children learning English

b. Results:

i. Children displayed cross-linguistic differences by 17-20 months of age

ii. Korean children extended ppayta to flat surfaces or tight clothing

iii. English children extended in to a position between two objects

c. Conclusion: Contradicts theories that children come equipped with domain-specific semantic primitives for space and spatial motion (e.g., Landau & Jackendoff, Behavioral and Brain Sciences 16, 1993)

Brown (2001 ‘Learning to talk about motion UP and DOWN in Tzeltal’ in Bowerman and Levinson, Language Acquisition and Conceptual Development)

Tzeltal Mayan has an Absolutive system of spatial reckoning based on the predominant uphill/downhill lay of the land (along a South (uphill)-North (downhill) axis)

Verb Position Relation

UP mo ‘ascend’ kaj ‘be above’ ajk’ol ‘uphill’

DOWN ko ‘descend’ pek’ ‘be low down’ alan ‘downhill’

e.g., ‘The rain is descending’ (i.e., coming from the south)

‘It (a puzzle piece) goes in downhillwards’

English has a Relative system of spatial reckoning (e.g., front/back, left/right)

Tzeltal children begin to use the Absolute vocabulary in the one- and two-word stage to refer to vertical relations (with verbs of falling and climbing) as well as horizontal relations (movement between houses or of toy cars on the flat patio)

The core semantics for the children’s verbs mo/ko are restricted at first to local places (particular houses in the local compound). The children generalize these verbs to novel contexts such as moving objects into trees, onto beds, up onto the roof, and to and from particular houses

Conclusions

Tzeltal children learn the language-specific constraints on verb use in context by a process of induction across instances of use, instances which provide both vertical contexts and landslope contexts for the same words

General lexicalization properties of the language rather than innate cognitive universals provide the basis for language-specific hypotheses about possible word meanings

Further examples of semantic specificity of Tzeltal verbs

|

|

Things you eat |

Tzeltal verbs |

|

|

bananas, soft things |

lo’ |

|

|

beans, crunchy things |

k’ux |

|

EAT |

tortillas, bread |

we’ |

|

tun |

meat, chilis |

ti’ |

|

|

sugarcane |

tz’u’ |

|

|

corn gruel, liquids |

uch’ |

Pye, Loeb & Pao (1996 ‘The Acquisition of Breaking and Cutting’ CLRF 27.227-236.)

Selectional restrictions on verbs are one of the main sources of semantic differences between languages. The breaking domain provides a good example of this variation. English speakers apply the word break to a wide array of objects: sticks, stones, bread, furniture, and machines. At the same time, English insists on marking the difference between breaking and tearing things. We break one and three dimensional objects, while we tear two dimensional objects.

|

|

Other languages break up this domain in different ways.

|

Object |

English |

Japanese |

Mandarin |

Spanish |

K’iche’ |

|

pen cap |

take off |

tor-u |

na xia |

quitar |

-esa:j |

|

apples |

pick |

tor-u |

zhai |

arrancar |

-ch’up |

|

cherries |

pick |

tzum-u |

zhai |

cortar |

-mak |

|

paper |

cut |

kir-u |

jian (kai) |

cortar |

-qopi:j |

|

string |

break |

kir-u |

duàn |

cortar |

-t’oqopi:j |

|

stick |

break |

or-u |

duàn |

quebrar |

-q’upi:j |

|

paper |

tear |

yabur-u |

xi (kai) |

romper |

-rach’aqi:j |

|

cracker |

break |

war-u |

bo (kai) |

romper |

-pi’i:j |

|

peanut |

break |

war-u |

bo |

pelar |

-paq’i:j |

English

Subjects: 16 American children (2;2-5:5)/22 adults (shown in parentheses)

Results: Percentage of children (adults) responding with break

|

% break |

hand |

ruler |

scissors |

string |

pencil |

|

toothpick |

1.0 (1.0) |

|

|

|

|

|

playdoh |

.87 (.23) |

|

.25 (-) |

.56 (-) |

.62 (-) |

|

peanut |

|

.62 (.5) |

.43 (.04) |

|

|

|

cracker |

|

.62 (.41) |

|

.62 (.59) |

.56 (.68) |

|

paper |

.56 (-) |

.44 (-) |

.31 (-) |

.37 (-) |

.56 (-) |

K’iche’

Subjects: 6 K’iche’ children (4;0)/5 adults (shown in parentheses)

Results: Percentage of children (adults) responding with q’upi:j

|

% break |

hand |

ruler |

scissors |

string |

pencil |

|

toothpick |

.7 (.8) |

|

|

|

|

|

playdoh |

.3 (-) |

|

.17 (-) |

.17 (-) |

.3 (-) |

|

peanut |

|

.17 (-) |

|

|

|

|

cracker |

|

.3 (-) |

|

.3 (-) |

.3 (-) |

|

paper |

.3 (-) |

.17 (-) |

.17 (-) |

.3 (-) |

.17 (-) |

Chinese

Subjects: 8 Chinese children (3;0-5;5)/13 adults (shown in parentheses)

Results: Percentage of children (adults) responding with duàn

|

% break |

hand |

ruler |

scissors |

string |

pencil |

|

toothpick |

.62 (.69) |

|

|

|

|

|

playdoh |

.25 (.77) |

|

.25 (-) |

.25 (.31) |

- (-) |

|

peanut |

|

.25 (-) |

.25 (-) |

|

|

|

cracker |

|

.25 (.15) |

|

.25 (.38) |

.12 (-) |

|

paper |

- (-) |

.25 (-) |

.25 (-) |

.25 (-) |

.12 (-) |