DESCRIPTION VS. EXPLANATION

On p. 54 Ingram introduces the distinction between a descriptive and explanatory stage (c.f. Brainerd 1978)

1. Descriptive Stage

a. some behaviors are observed to undergo change

b. antecedent variables (causes) are proposed to account for the change

2. Explanatory Stage

a. some behaviors are observed to undergo change

b. antecedent variables are proposed to account for the change

c. an independent measure of the antecedent variables is established

What examples of descriptive and explanatory stages does Ingram provide?

What types of independent evidence does Ingram discuss?

Positive and Negative Evidence

a. Children only draw upon positive evidence to acquire language

positive evidence: evidence available in input, e.g., irregular verb past tense, went

b. Children do not acquire language on the basis of negative evidence (two types)

i. direct negative evidence: correction by parents (Braine p. 29)

Child: Want other one spoon, Daddy.

Father: You mean, you want the other spoon

Child: Yes, I want other one spoon, please, Daddy.

Father: Can you say ‘the other spoon’?

Child: Other ... one ... spoon.

Father: Say ... ‘other’.

Child: Other

Father: Spoon

Child: Spoon

Father: Other ... spoon

Child: Other ... spoon. Now give me the other one spoon.

ii. indirect negative evidence: child computes input frequencies and notes what has not occurred.

References

Braine, M. D. S. 1971. On two types of models of the internalization of grammars. In D. I. Slobin (ed.), The Ontogenesis of Grammar, pp. 153-186. New York: Academic Press.

Chouinard, M. and E. Clark. 2003. Adult reformulations of child errors as negative evidence. Journal of Child Language 30: 637-669.

Marcus, G. 1993. Negative evidence in language acquisition. Cognition 46: 53-85.

Saxton, M. 1997. The contrast theory of negative input. Journal of Child Language 24: 139-161.

Saxton, M. 2000. Negative evidence and negative feedback: Immediate effects on the grammaticality of child speech. First Language 20: 221-252.

Zwicky, A. 1970. A double regularity in the acquisition of English verb morphology. Working Papers in Linguistics 4. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University.

Universal Grammar—Parameters

Linguists have long assumed that children’s access to Universal Grammar (UG) explains their ability to acquire any human language (Chomsky 1965). This assumption has become difficult to maintain in the absence of concrete examples of linguistic universals.

Newmeyer (2004, 2005) reviews the arguments that have been given in favor of parameters and argues that parameters have no advantage over linguistic rules.

Newmeyer’s arguments:

a. Parameters are descriptively simple

Parameters are supposedly more general than rules, but linguists use the term parameter as a synonym for rule (Cinque 1994). Parametric accounts still acknowledge the need for rules, e.g. the account of Hixkaryana OVS word order as S[OV] parameter + VP fronting rule

b. Parameters have binary settings

There is no evidence of binarity in morphosyntax, e.g. gender, number, case.

c. Parameters are small in number

A single issue of Linguistic Inquiry may contain 30-40 proposed parameters (Lightfoot 1999:259)

Newmeyer provides the following estimate for the number of functional heads:

a. 32 in the IP domain (Cinque 1999)

b. 30 for DP (Longobardi 2003)

c. 5 for Adjective Phrase

d. 12 or more for CP (Rizzi 1997)

e. 4 for clitic inversion (Poletto 2000)

f. 6 for thematic roles (Damonte 2004)

g. 4 for Neg phrase (Zanuttini 2001)

d. Parameters are hierarchically/implicationally organized

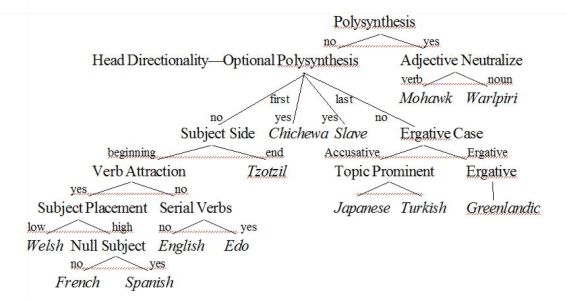

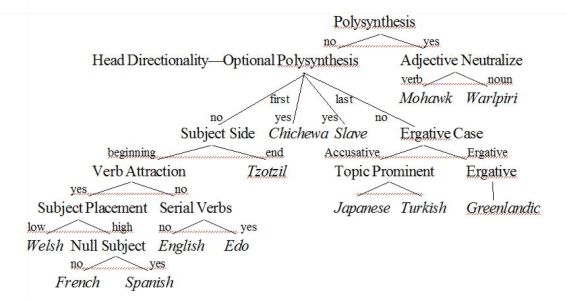

There is little published work on the implicational organization of parameters with the exception of Mark Baker’s (2001) ‘The Atoms of Language’. Baker proposes the Parameter Hierarchy (PH) shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Parameter Hierarchy (Revised) (Baker 2001:183)

The PH’s predictions about frequency do not hold, e.g. polysynthetic vs. nonpolysynthetic. It also predicts that null subject languages will be rare.

The PH is a revival of the holistic typological approach that tries to isolate language types, but it is clear that typological properties crossclassify with one another rather than being organized hierarchically.

e. Parameters predict unexpected clusterings of morphosyntactic properties

Parametric properties do not cluster together across unrelated languages, e.g. pro-drop.

Many studies that propose parameters only examine a single language. Rule-based accounts handle clustering within a single language just as easily.

f. Parameters are innate

The absence of parameters has no bearing on innateness. Parameter theory is one argument for UG; the other comes from poverty of the stimulus arguments.

g. Parameters are easier to learn than rules

Exposure to utterances isn’t sufficient to set parameters, e.g. the 32 IP projections for adverbs

There is no common feature in English, Chinese and Japanese that children can use for the negative setting of the ergative parameter.

Children need to have their grammar in place to benefit from triggers, e.g. expletives.

Children have to acquire the hard stuff at the periphery anyway so parameters don’t add any benefit.

There is no psycholinguistic evidence of a difference between core and periphery.

Children acquire language-specific structures early, regardless of their rarity.

Another problem children face is learning which principles or parameters apply in specific linguistic contexts. An innate knowledge of principles and parameters does not provide information about their application to features in specific languages.

h. Parametric change is different than rule-based change

There is no evidence to support Lightfoot’s claims for parametric change.

Newmeyer claims that parameters can be replaced by independently needed principles of performance.

Newmeyer, Frederick J. 2004. Against a parameter-setting approach to typological variation. Linguistic Variation Yearbook 4.181-234.

Newmeyer, Frederick J. 2005. Possible and Probable Languages: A Generative Perspective on Linguistic Typology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Universal Grammar—Arguments from the Poverty of the Stimulus

The Argument from the Poverty of the Stimulus remains the primary evidence for innate knowledge of language. Chomsky has long claimed that an innate knowledge of linguistic principles and parameters is necessary to explain how children acquire language from the primary linguistic data. Fodor (1981) claims that “The APS is the existence proof for the possibility of cognitive science.”

Example arguments:

i. Yes/no-question formation (Chomsky 1975:32; c.f. Ingram p. 66)

The man who is tall is in the room.

Is the man who is tall t in the room?

* Is the man who t tall is in the room?

ii. dative acquisition (Baker 1979, originally proposed in Braine 1971), p. 28

I gave the book to Mary

I gave Mary the book

I said some things to Mary

* I said Mary some things

iii. wanna-contraction (Guasti, p. 9, but see Pullum 1997, O’Grady 2005; wanna is a morphological derivation, not syntactic, and therefore children can use lexical learning, not UG. Want is a ‘subject-to-object’ raising verb like consider, so the difference is between who as the object of invite and who as the object of want. Warren, Spear & Schafer (2003) report that speakers consistently lengthen want in contexts where the contraction is blocked. They are also more likely to pause after want in these contexts.)

Who do you wanna invite?

When do you wanna come?

* Who do you wanna come?

iv. Negative Polarity Items (Crain & Pietroski 2002)

No linguist has any brains.

Every linguist with any brains admires Chomsky.

* Every linguist has any brains.

v. “Inclusive or” interpretations (Crain & Pietroski 2002)

Eat your veggies or (exclusive) you won’t get any dessert.

No one with any brains admires linguists or (inclusive) philosophers.

Every linguist or (inclusive) philosopher with any brains admires Chomsky.

Everyone admires a linguist or (exclusive and inclusive) philosopher.

vi. Pronoun interpretation; Principle B (Crain & Pietroski 2002)

Hei said the Ninja Turtle*i/j has the best smile. (pronoun c-commands NP)

As hei was leaving, the Ninja Turtlei/j smiled. (pronoun does not c-command NP)

Who did he say has the best smile?

Whoi did hej say has the best smile? (Deictic Pronoun Reading)

*Whoi did hei say has the best smile? (Bound Pronoun Reading)

Who said he has the best smile?

Whoi said hej has the best smile? (Deictic Pronoun Reading)

Whoi said hei has the best smile? (Bound Pronoun Reading)

vii. that-trace effect (Haegeman 1994)

Who did he think was available?

*Who did he think that was available?

He thought that Sally was available.

Pullum & Scholz (2002:9-50) analyzed the Poverty of Stimulus (POS) arguments and distill the following points about the acquisition process and children’s language environment that are used to support POS arguments:

(1) Properties of the child’s accomplishment

a. SPEED: Children learn language so fast.

b. RELIABILITY: Children always succeed at language learning.

c. PRODUCTIVITY: Children acquire an ability to produce or understand any of an essentially unbounded number of sentences.

d. SELECTIVITY: Children pick their grammar from among an enormous number of seductive but incorrect alternatives.

e. UNDERDETERMINATION: Children arrive at theories (grammars) that are highly underdetermined by the data.

f. CONVERGENCE: Children end up with systems that are so similar to those of others in the same speech community.

g. UNIVERSALITY: Children acquire systems that display unexplained universal similarities that link all human languages.

(2) Properties of the child’s environment

a. INGRATITUDE: Children are not specifically or directly rewarded for their advances in language learning.

b. FINITENESS: Children’s data-exposure histories are purely finite.

c. IDIOSYNCRASY: Children’s data-exposure histories are highly diverse.

d. INCOMPLETENESS: Children’s data-exposure histories are incomplete (there are many sentences they never hear).

e. POSITIVITY: Children’s data-exposure histories are solely positive (they are not given negative data, i.e. details of what is ungrammatical).

f. DEGENERACY: Children’s data-exposure histories include numerous errors (slips of the tongue, false starts, etc.).

P&S (19) discern five points that must be proved for a poverty of stimulus argument to be true:

i. ACQUIRENDUM CHARACTERIZATION: describe in detail what is alleged to be

known.

ii. LACUNA SPECIFICATION: identify a set of sentences such that if the learner had access

to them, the claim of data-driven learning of the acquirendum would be supported.

iii. INDISPENSABILITY ARGUMENT: give reason to think that if learning were

data-driven then the acquirendum could not be learned without access to sentences in the lacuna.

iv. INACCESSIBILITY EVIDENCE: support the claim that tokens of sentences in the lacuna

were not available to the learner during the acquisition process.

v. ACQUISITION EVIDENCE: give reason to believe that the the acquirendum does in fact

become known to learners during childhood.

Pullum & Scholz claim that no one has produced a poverty of stimulus argument that successfully addresses all five of these points. They begin with a logical argument against the POS argument made by Sampson (1989, 1999a) that goes:

Consider the position of a linguist - let us call her Angela - who claims that some grammatical fact F about a language L has been learned by some speaker S who was provided with no evidence for the truth of F. Sampson raises this question: How does Angela know that F is a fact about L? If the answer to this involves giving evidence from expressions of L, then Angela has conceded that such evidence is available, which means that S could in principle have learned F from that evidence. That contradicts what was to be shown. If, on the other hand, Angela knows L natively, and claims to know F in virtue of having come to know it during her own first-language acquisition period with the aid of innate linguistically-specific information, then Angela has presupposed nativism in an argument for nativism (15).

P&S claim that Haegeman’s argument from the that-trace effect is based on a false claim about the nature of the ACQUIRENDUM. Rather than learning to rule out ‘V + that + finite VP’ sequences such as *Who did they think that was available? children instead learn ‘N + that + finite VP’ sequences such as things that were available. Children never hear ‘V + that + finite VP’ constructions so they do not produce them. P&S (16) suggest children may not be learning the type of movement rule that is the basis for Haegeman’s argument.

P&S suggest that an argument made by Lightfoot (1998:585) has a similar problem. Lightfoot claims that children might be misled into overextending contraction to sentences like *Kim’s taller than Jim’s. P&S (17) observe that if children learn that contraction only applies in stressless contexts they will not apply contraction to cases where the VP head has weak stress.

Gordon (1986) and Pinker (1994) also misanalyzed the ACQUIENDUM in claiming that noun compounds can only have irregular plural modifiers (mice-catcher, teeth eater), but P&S cite many counter-examples (forms-reader, securities-dealer, drinks trolley, rules committee, complaints department).

P&S (27) cite an argument by Kimball that ‘English-speaking children will acquire the full auxiliary system . . . without having heard sentences directly illustrating each of the rules’ (1973: 74). Kimball claims that ‘sentences in which the auxiliary is fully represented by a modal, perfect, and progressive are vanishingly rare’ illustrating the INACCESSIBILITY EVIDENCE part of the argument. P&S (28-29) cite many examples in which the full auxiliary is present to suggest that Kimball’s claim lacks credibility.

Baker (1978:413-425) claimed that one serves as an anaphor for a constituent smaller than a noun phrase:

This box is bigger than the other one.

Baker also claims evidence for this possibility is unavailable to children. P&S question the accuracy of Baker’s linguistic claim (ACQUIRENDUM) as well as the claim that children lack evidence for one’s usage (INACCESSIBILITY) citing (36) the following dialogue:

A: "Do you think you will ever remarry again? I don't."

B: "Maybe I will, someday. But he'd have to be somebody very special. Sensitive and supportive, giving. Hey, wait a minute, where do they make guys like this?"

A: "I don't know. I've never seen one up close."

P&S (39-40) claim that Chomsky’s yes/no-question example rests on a claim about the absence of relevant examples in the input (INACCESSIBILITY). They cite many examples to the contrary (40-44). Chomsky’s argument also ignores the semantics of yes/no questions and the discourse function of relative clauses (Hausser 2004:921). Relative clauses provide background information while questions focus on elements in the foreground:

* What did Robin give a pencil to the woman who found ___ ?

* Are the people who ___ on the bus look tired?

* How did the car that drove ___ was parked?

Bibliography on the Poverty of Stimulus Argument

Baker, C. L. 1979. Syntactic theory and the projection problem. Linguistic Inquiry 10: 533-581.

Braine, M. D. S. 1971. On two types of models of the internalization of grammars. In D. I. Slobin (ed.), The Ontogenesis of Grammar, pp. 153-186. New York: Academic Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 1975. Reflections on Language. New York, New York: Pantheon.

Clark, Alexander & Shalom Lappin. 2011. Linguistic Nativism and the Poverty of the Stimulus.

Chichester, United Kingdom: Wiley-Blackwell.

Cowie, F. 1999. What’s Within? Nativism Reconsidered. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Crain, Stephen and Paul Pietroski. 2002. Why Language Acquisition is a Snap. The Linguistic Review 2002.

Fodor, J. A. 1981. Representations. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Haegeman, Liliane. 1994. Introduction to Government and Binding Theory. 2nd edition. Oxford, U.K. and Cambridge, MA: Basil Blackwell.

Lasnik, Howard and Juan Uriagereka. 2002. On the poverty of the challenge. The Linguistic Review 19: 147–150.

Levine, Robert D. 2002. Review of Juan Uriagareka, Rhyme and Reason. Language 78:325-330.

Legate, Julie Anne and Yang, Charles D. 2002. Empirical re-assessments of stimulus poverty arguments. The Linguistic Review 19:151-162.

MacWhinney, Brian. 2004. A multiple process solution to the logical problem of language

acquisition. JCL 31:883-914.

O’Grady, William. 2005. Syntactic Carpentry: An Emergentist Approach to Syntax. Mahwah: NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Pinker, Steven. 1994. The Language Instinct. New York: William Morrow.

Pullum, Geoffrey. 1996. Learnability, hyperlearning, and the poverty of the stimulus. Paper pre-sented at the Parasession on Learnability, 22nd Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society, Berkeley, CA.

Pullum, Geoffrey. 1997. The morpholexical nature of to-contraction. Language 73: 79-102.

Pullum, Geoffrey and Barbara Scholz. 2002. Empirical assessment of stimulus poverty arguments. The Linguistic Review 19: 8–50.

Sampson, Geoffrey. 1989. Language acquisition: growth or learning? Philosophical Papers 18:203–240.

-----. (1999a). Educating Eve. London: Cassell.

-----. (2002). Exploring the richness of the stimulus. The Linguistic Review 19: 73–104.

Valian, Virginia. 2009. Innateness and learnability. In E. Bavin (ed.), Handbook of Child Language, pp. 5-34. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Warren, Paul, Shari Speer & Amy Schafer. 2003. Wanna-contraction and prosodic disambiguation in US and NZ English. Wellington Working Papers in Linguistics 15:31-49.