Ling 107

Writing

Oral language is a natural trait of humans

It’s species specific

It’s not taught

In contrast, written language must be taught

It’s hard to learn—many people fail to learn written forms

This contrast shows that writing systems are not simple transcriptions of oral language

They require extra processing—> ‘interpretation’

Oral language is universal among humans

Like the wheel, written language has features of a cultural rather than a biological attribute.

Written language was invented independently in just 5 places:

Egyptian, Sumerian, Harappan (India), Chinese & Mayan (Epi-Olmec)

These writing systems have a similar developmental history.

Ideographic Writing (idea writing)—Each symbol conveys a general idea.

Ideographic writing uses stylized pictures to convey a limited number of conventional meanings. In this sense, ideographic writing does not count as a real writing system since it cannot be extended indefinitely.

Ideographic writing appeared 20,000 years ago in early paleolithic cave paintings. Here is a detail from the cave paintings at Lascaux France.

Another example is the winter count maintained by Lone Dog of the Yankton band of Dakotas. Each symbol records an event from 1800-1871.

It is impossible to interpret the symbols in either of these texts without an interpreter. For example, the symbol

records an attack on an Arikara fort in 1823-24 by U.S. soldiers. (Garrick Mallery's Picture-Writing of the American Indians, 1893, pp. 266-287.)

Ideographic writing still has many uses in our society. Think of the signs you see along roads.

Logographic Writing (word writing)—Each symbol represents a word.

The step from ideograph to logograph adds greater flexibility to a writing system. Although there is still a close association of symbol and idea in a logograph, the idea is fixed to a specific word. The Egyptian logograph for the word ziçiR, meaning “write” shows a picture of a scribe's tools

Many Chinese characters can be traced back to their ideographic origins.

When used over long periods of time logographs become more simplified and less iconic. Of course, it doesn’t hurt to know what an Egyptian scribe’s tools looked like in the first place!

A logograph attempts to represent meaning rather than sound. The next step in the development of writing occurred when scribes began using logographs to represent sounds.

Syllabic Writing—Each symbol represents a syllable.

If the goal of a writing system is to represent the spoken message, the step from representing meaning to representing sounds seems to take writing in the wrong direction. What syllabic writing loses in iconicity, though, is more than compensated for by efficiency.

Here's the word watakushi, meaning "I" (a polite form) in the hiragana syllabary of Japanese.

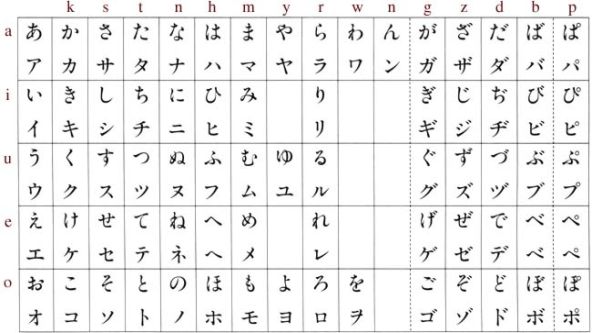

Japanese has two syllabaries:

Hiragana for native words including suffixes

Katakana for foreign words

This chart shows both sets of syllabic symbols (the hiragana symbols are on top).

While syllabic writing works well for some languages, it encounters problems when used with other languages. What problems would you have in using syllabic writing for English?

The solution to these problems is to develop the means of representing individual phonemic segments.

Alphabetic Writing—each symbol represents a speech sound.

The Egyptian writing system was partly alphabetic, though originally it indicated only consonants (like the Semitic alphabets that probably descended from Egyptian writing).

An example is the word twt, meaning “image.” The little loaf of bread represents the sound [t], and the quail chick for the sound [w].

This is the first syllable of the name Tutankhamun, or the “living image of Amun.”

Origins of Writing

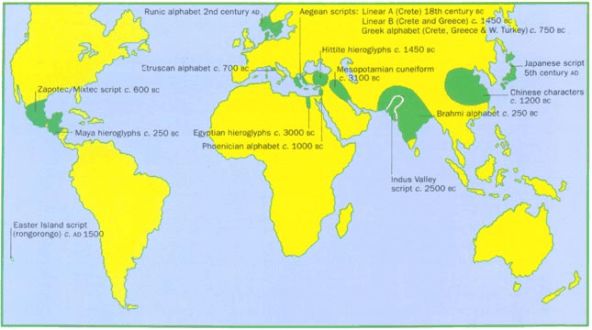

The following map shows where and when a number of writing systems first appeared.

Writing may have originated in only four or five societies around the world. The Sumerians, Egyptians and Chinese are given credit for independently inventing writing, but a glance at the characters in Figure 8 (p. 453) shows many similarities between their early pictographs.

Ancient Mesopotamian system is the best documented.

Denise Schmandt-Besserat theorized that Mesopotamian writing originated in need to record business shipments.

Clay tokens were used from 8000 BCE in Mesopotamia for some form of record-keeping. sent with actual goods—sheep, pots, etc.

Kept in hollow clay balls to guard against theft

Eventually traders began making impressions of the tokens on the outsides of the balls

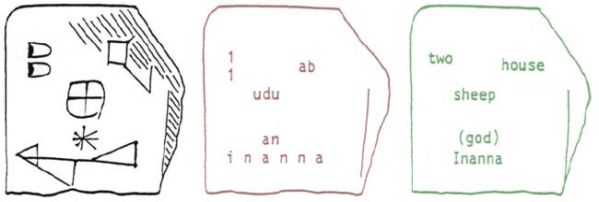

Led to the emergence of logographic writing sometime between between 3200 and 3000 BCE. The Sumerians developed a system of icons inscribed on clay tablets for keeping temple economic records.

This example shows the icons for “two”, “sheep”, “house” (also “temple”), and the goddess “Inanna” with the general symbol for “god” used to identify divine beings.

Over centuries the characters were simplified to suit the clay writing medium

A wedge-shaped stylus was pressed into the clay—cuneiform (< Lat. cuneus ‘wedge’)

Such ideographic scripts are perfectly suited to keeping track of simple objects, but they begin to run into trouble when used to write about more abstract matters. A common practice is to extend an ideograph to words that sound like the original, creating a rebus.

The world's first clear example of rebus comes from a Jemdet Nasr tablet dated to around 2900 BCE. The picture of the concrete object gi “reed” was used for the abstract verb “reimburse.”

gi “reed”

gi “reimburse”

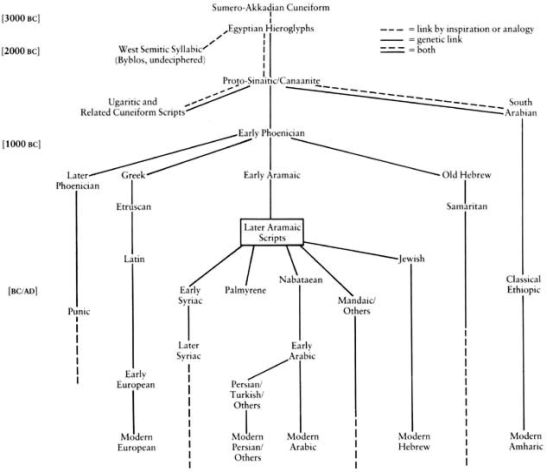

Writing emerged independently in at least three places: Mesopotamia, China and Mesoamerica. In each case writing begins with pictograms for mnemonic aids in record keeping, or as vehicles of insight in divination. The number of signs inevitably increases, leading to the use of some signs as rebuses or as phonological/semantic combinations. Once this meaning-plus-sound emerges, it rapidly develops into a (partly) phonetic writing system, able to record any text in the language. We can trace our own alphabet back to those original Mesopotamian clay tokens.

Deciphering Ancient Scripts

Deciphering ancient writing also brings linguistic principles into play. The number of characters in a script provides an important clue to the type of writing system being used (Coe 1992, 43):

|

Writing System |

Number of Signs |

|

Logographic |

|

|

Sumerian |

600 + |

|

Egyptian |

2,500 |

|

Chinese |

5,000 + |

|

Syllabic |

|

|

Linear B |

87 |

|

Cherokee |

85 |

|

Alphabetic |

|

|

English |

26 |

|

Sanskrit |

35 |

|

Etruscan |

20 |

|

Russian |

36 |

Writing systems usually include a way of showing inflections for grammatical features such as number, person, and tense or aspect. These can be expected to occur more frequently than nouns or verbs. If you find some signs that occur with high frequency in a text, there is a high probability that they indicate an inflection.

Egyptian Hieroglyphics

The decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphics is well known (Stephanie Rossini, 1989)

Hieroglyphics were used for 3,500 years before they were banned by the Christian Roman emperor Theodosius in 384 A.D.

They weren’t read again for another 1,400 years

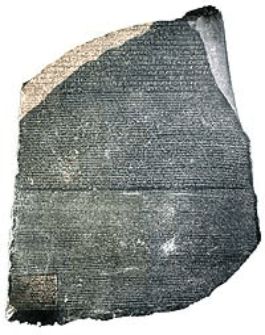

French unearthed a black basalt stela in 1799 near Rosetta

It was a decree in honor of King Ptolemy V written in 196 B.C.

Written in Greek, demotic (simplified hieroglyphs), and hieroglyphs

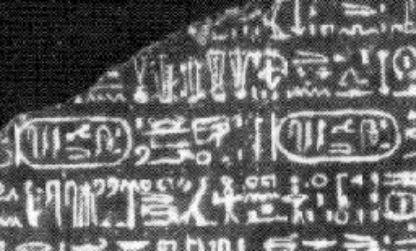

Jean Francois Champollion (1790-1832) in1822 matched the hieroglyphs in the oval frames(cartouches) with the Greek names of the Egyptian kings. Here is a detail from the Rosetta stone showing two cartouches for Ptolemy.

You should be able to work out many of the phonetic values for PTOLMYS from the following table

Comparing the cartouches for Ptolemy and Cleopatra showed the letters the two names have in common. Champollion found the hieroglyphs contained a mix of alphabetic, syllabic and logographic writing

Mesoamerican Writing

A similar fate befell the Mayan hieroglyphic writing system (Michael D. Coe, 1992, Breaking the Maya Code)

The first New World hieroglyphs occur on Olmec and Zapotec monuments around 600 B.C. This is a Zapotec monument from San José Mogote

First found in the Mayan area between 100 B.C. and 100 A.D.

Then spread throughout the Maya area during the Classic Period (300-900 A.D.)

The collapse of Mayan cities (900 A.D.) also brought the end of historical monument carving

But Mayan writing continued until the Spanish conquest (1520)

Survived in Chitzen Itza up till 1700

Find examples of hieroglyphic writing in bark paper books—only 4 survive

Diego de Landa, 3rd bishop of Yucatan caused his share of the destruction

His ‘An Account of the Things of the Yucatan’ (1566) describes burning Mayan books and the weeping this caused among the populous

The burning was part of his inquisition

Fortunately, Landa included an example of the Mayan ‘alphabet’ in his account

This is a classic example of cultural miscommunication

Landa wanted an example of the Mayan word le ‘a noose, hunt with noose’

He assumed Mayan alphabet had the letters ‘l’ and ‘e’

So he asked his consultant to write ‘l’, ‘e’, and ‘le’

in Spanish ‘l’ is [ele], therefore got [ele e le]

Next Landa asked for the word for water, ha

in Spanish ‘h’ is [ache], therefore got [ache a ha]

By this time both men were getting frustrated with one another

Landa asked his consultant to write something else and got ‘I don’t want to’

Landa’s alphabet is the closest thing to a Rosetta Stone that Mayanists are likely to find

Landa’s key was first recognized by a soviet researcher, Yuri Knorosov, in 1950s

Knorosov’s discoveries were again affected by cultural miscommunication; this time due to the marxist-leninist polemics they contained

Just what you’d expect from a young Soviet scientist in the Stalinist era.

The polemics insured that his work would remain obscure in the West until 1980s

Knorosov recognized the syllabic quality of Mayan writing

The glyphs represent CV combinations

However most Mayan words have a CVC structure

Knorosov thought Maya used a second glyph to represent the final C, and didn’t say its vowel

The vowel in the second glyph should be the same as the vowel in the first glyph

Called the principle of synharmony

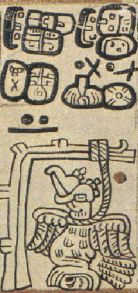

Applied his principle to one of the glyphs in the Madrid Codex (p. 91).

ku tz(u)

kutz

“turkey”

He then applied method to glyphs for dog tzul from the Dresden Codex (p. 21).

tzu l(u)

tzul

“dog”

The second glyph was Landa’s lu

More than half of the syllabic signs are recognized today

Others don’t occur frequently enough to allow for a secure decipherment

Still don’t know the values of some of the glyphs in Landa’s alphabet

His consultant was hard pressed to come up with equivalents for Spanish alphabet and used rare or unique examples

Also find many variations and styles of Mayan hieroglyphs

Used many logographic signs for gods, place names

Mayan scribes employed the rebus principle

kan sky sign was also used for the number four

Find multiple component glyphs that represent one word, but contain affixes

Glyphs also have geometric and personified forms—just head or full figure, animal or human

It is difficult to determine which features are critical for distinguishing one glyph from another

and which are just stylistic variants

Just as knowledge of the Mayan writing is rapidly expanding

Archeological remains are rapidly disappearing into the illegal art market

This removes examples of hierglyphic writing from their original context and renders them useless for future decipherment—so don’t do it!

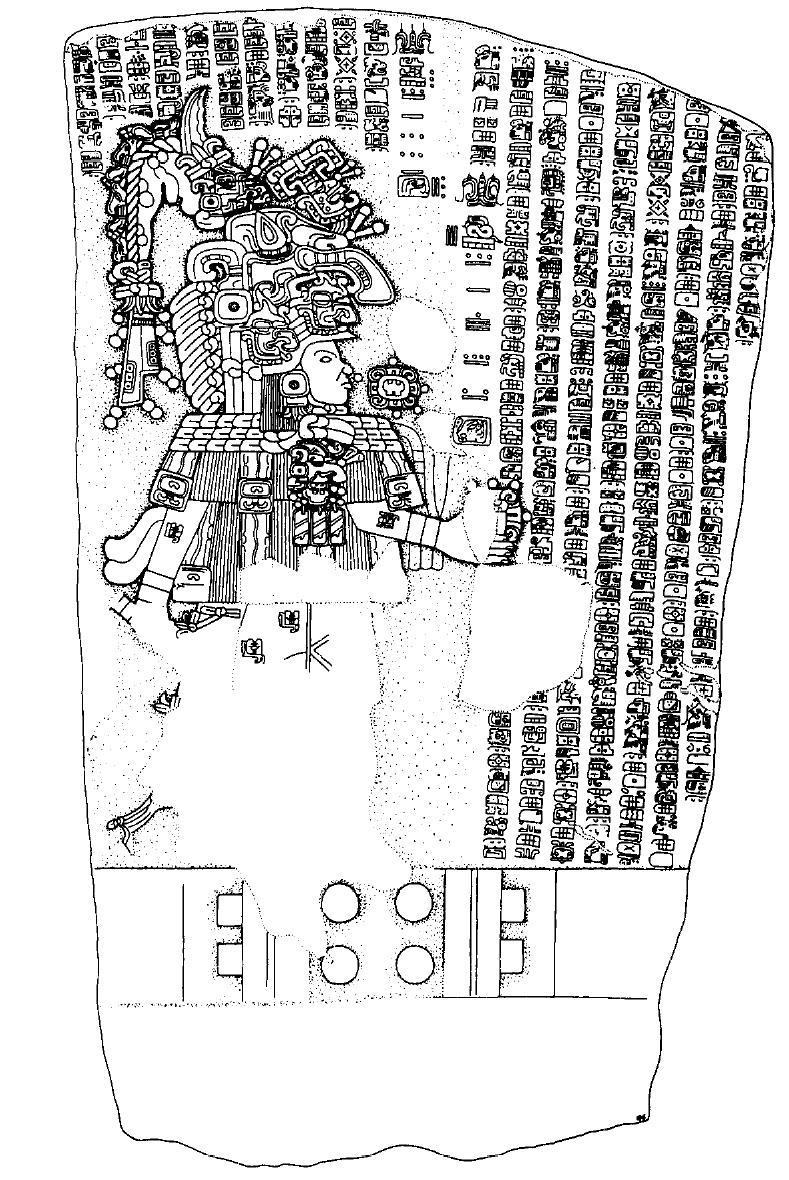

Yaxchilan Stela 11

Stella 11 from the Yaxchilan site provides a good idea of what the classical Mayan inscriptions were like.

Yaxchilan Stela 11, front lower register

Date

ISIG (Tzek). 9 baktuns. 16 katuns. 1 tun. 0 winals. 0 kins

11 Ahaw 8 Tzek

G9 F Z 12 D 5 E X B 9 A

Verb

u hok’-ah

3Erg took_office-Completive

Preposition

(ti) ti

as

Subject

Ahpo le ___/b’alam, u chan Ah Kwak

Lord Bird-Jaguar, his captor Ah Kwak

3 katun ___ ch’ak te ch’ul Ahpo Yaxchilan I/ch’ul Ahpo Yaxchilan II

3 katun Ruler devine Lord Yaxchilan II/devine Lord Yaxchilan II

Ya-al na Na Ik Kimi chan na Na ch’ul ___ na Na b’akab’a

child of Lady Ik-Skull sky house Lady devine God C Lady Bakab

u ch’ok u ___ ___ ___ 5 katun Ahpo Pakal B’alam

3Erg child 3Erg child 5 katun Lord Shield Jaguar

u chan ah Ahpo la ch’ul Ahpo Yaxchilan I/ch’ul Ahpo Yaxchilan II b’akab’a

his captor Lord devine Lord Yaxchilan I/devine Lord Yaxchilan II bakab

In plain English

Nine bak’tuns, 16 kat’uns, 1 tun, 0 winals, and 0 k’ins after the beginning of the current era on the day 11 Ahaw [when the ninth Lord of the Night closed the headband; when the lunation was twelve days old after five lunations (in the current cycle of six) had been completed; X was the name of the twenty-nine day lunation] on the day 8 Sek acceded as Ahaw, Bird Jaguar, Captor of Ah Uk, He of 21 Captives, The 3 K’atun Chakte, The Divine Yaxchilan Ruler. He is the child of Lady Ik’ Skull, Sky Lady, She of the Holy Books, Lady Bakab. He is the child of The Scatterer, The 5 K’atun Ruler, Shield Jaguar, Captor of He the Flower, Divine Yaxchilan Ruler, Bakab’ (Harris & Stearns 1997:173).

Wikipedia provides an introduction to the Mayan calendar.

Epi-Olmec Writing

Terrence Kaufman and John Justeson are in the process of deciphering an Epi-Olmec text found on Stela I at La Mojarra.

La Mojarra Stella I. Drawing by George E. Stuart.

You can read their article to learn about their method of decipherment.

La Mojarra Stella I Text

(from Justeson & Kaufman 1993)

A ISIG.?.3 ‘ame.8.5.3.3.5.13 snake

B .?.?.?.7ips.ju7tz.ma.pak.ku.wʉ

.x.x.x.20.pierce.x.beat.x.CP

C .ma.matza7.tza7.kij.wʉ.kij.ji.wʉ

.PD.star.PD.shine.CP.shine.PD.CP

Fig 7C

‘The star shone.’

D .tza7.ma.sa.wik.?.ma

E .?.?.wʉ.kak.?

.royal title.royal title.REL.x.x

F .ta.ma.7i.ki.pi.wʉ

tam 7i-kip-wʉ

Fig 6A

‘adverb he fought him’

G .ma.ja.ma.?.ja.ma.na

ma jama x jama na

‘days ago, day/nagual’

H .ki7m.wʉ.7i.si

ki7m-wʉ 7isi

Fig 6E

‘he ascended lo!’

I .13.7ame.pit.ti.jʉsa7ka.?

.13.year.with.PD.and then.x

‘in the 13th year

J .?.6.po.7a.wʉ.7o.tu.pa

x 6 poy7a-wʉ 7otuw-pa

Fig 6H

‘he who is 6 moon speaks’

K .na.kʉ.tu.si.tzi.si.wʉ

na-kʉ-tus-i-tzi-si-wʉ

I-x-stand?-x-give-x-CP

‘I stood and gave it’

L .?.tuk.?.na.tze.tze.tzetz.ji.ma.wʉ

? tuk ? na-tzetz-ji7m-wʉ

Fig 7G

.name.title.title.I.chop.do-CP

‘I did a chopping’

M .ki7m.je.tzi.te.7i.si.wʉ ISIG.15 snake.8.5.16.9.7.5 mʉ7a

ki7m-jetz 7isi-wʉ Fig 8B Fig 8B

Fig 6E 15 snake 5 deer

‘he acceded lo!’ month day

N .4.poy7a.?.ma.7i.ki7m.7ame.pit.wik.wʉ.7i.?.naka.7ame.?.je.?.pe.wʉ

4 poy7a x ma 7i-ki7m 7ame-pit wik-wʉ 7i-x naka 7ame x x-wʉ

4 moon x ago he-accede year-at scatter-CP he-drops skin year replace title REL

‘4 months ago he accedes. At the year he scattered the skin’s drops the year he replaced title’

(20) .38.51.38.83.38.?.67.

.7i.?.7i.?.7i.ku.kuk.tza.ja.me

7i-x 7i-x 7i-kuk-tzaj-me

his-title his-status he-middle-x-x

(30) . .161.20

.ja.wʉ-tzʉk.wʉ.ju7tzi.?.ko.komi.?.wʉ.?

x wʉ-tzʉk-wʉ ju7tzi x ko-komi x-wʉ

x array-CP and_then x other-lord x-REL

‘arrayed and then he was lord of others’

O .13.jam.ma.?.?.kak.kakpe.pe.?tuk.?.ki7m.?.?.wʉ.7aw.ki7m.mʉ.tza.pa.

13 jama x x kakpe x tuk x ki7m x x-wʉ 7aw-ki7m-ʉ tzap

Fig 7G Table 3 Fig 6I

13 day god Long Lip scorpius king title accede throne reveal-CP authority sky

‘on the 13 day god Long Lip in Scorpius the king acceded to the throne and revealed the divine quetzal authority’

(20) ?.ko.ki7m.mi.?.?.?.na

x ko-ki7m x x x

quetzal other-rule x holy town

‘of the holy town’

(27) naks.wʉ.7ame.wi.?.paks.pa.tu.ku.7i.ju7tz.si.7i.7o.tu.pa

naks-wʉ 7ame wis x paks-pa tuku 7i-ju7tz-i 7i-7otuw-pa

Fig 6H

pound-CP year uproot? x fold-IP cloth he-pierce-ID he-speak-IP

‘pounded the year, uproot x, folds cloth, he pierces, he speaks’

P(3) .na.nʉ7pin.7i.ko.tokoy.pʉ.wʉ.?.7aw.ki’m.?.?.kak.?.?.tuku.tuj.ma

na-nʉ7pin 7i-ko-tokoy-pʉ-wʉ x 7aw-ki7m x x kak x x tuku tuj ma

my-blood he-other-lose-x-CP status authority x time x crown cloth rain

‘my blood he lost for others (for) the status of authority. At the time of the cloth crown rain’

(23) .ko.ju7tz.kʉ.wʉ.7i.ki7m.si.7i.?.?

ko-ju7tz-kʉ-wʉ 7i-ki7m-ʉ si7i

Fig 6C

other-pierce-begin-CP he-rule-CP back

‘his royal back began to get pierced for others’

(33) .?.kan.joj.mʉ.kʉ.?.wʉ.ju7tzi.pʉk.7i.7o.wa

x kan-joj-mʉk x-wʉ ju7tzi pʉk 7i-7owa

Fig 6J, Table 2

let_blood penis-inside-from title-REL and_then receive his-macaw

‘he of the title let blood from inside the penis, and then received his macaw’

Q .ju.si.ma.ke.ne.paks.pa.tuku.?.?.wʉ.?.ko.komi.?.?.tuk.?.7i.ko.te.kʉ

jusima kene paks-pa tuku x x-wʉ x ko-komi x x tuk x 7i-kotekʉ

x x fold-IC cloth x status-REL x other-lord title king x title his-x

Fig 7G

‘he of status folds the cloth. The king of title is lord of others’

(22) ju7tzi.matza7=ju7tz.konu7ks.wʉ.te.wan.ne.tzʉk.pa.ja.ma.wʉ

ju7tzi matza7=ju7tz konu7ks-wʉ te wane tzʉk-pa jama-wʉ

and_then star=pierce hallow-CP the song do-IP nagual-REL

‘and then he hallow star-pierced and he who is nagual did the song’

(34) .ju7tzi.na.kan.pʉk.ma.jup.pu.?.7a.kak.kakpe.pe.ki7m.wʉ

ju7tzi na-kan pʉk ma jup x kakpe ki7m-wʉ

and_then my-penis receive? x tie x scorpius rule-CP

‘and then my penis received x and tied when scorpius ruled’

(48) .ju7tzi.ko-pak.kajaw.?.wʉ

ju7tzi kopak kajaw x-wʉ

and_then head jaguar reveal-CP

‘and then the jaguar head revealed’

R .pak.ku.ma.matza7.tza7.matza7.wʉ

paku ma matza7 matza7-wʉ

x x star shine-CP

‘x the star shone’

(9) .?.?.9.ja.ma.kajaw.pʉk.kʉ.7i.naka.7ame.?.yʉ

x x 9 jama kajaw pʉk 7i-naka 7ame x yʉ

day_count x 9 day jaguar receive his skin year replace

‘on the day 9 jaguar receive his skin year and replace

(22) .?.?.?.?.7ame.ji7tzʉ7.7i.ne.ji.jam.kipsi.si

x x x x 7ame ji7tzʉ7 7i-neji jam kipsi

governor hallow title title year longlip x symbol

‘governor hallow title title (in) year longlip’

(34) .7i.tokoy.?.7i.ki.pi.wʉ.7i.nʉ7pin.2.7i.nʉ.si.?.we.pa

7i-tokoy x 7i-kip-wʉ 7i-nʉ7pin 2 7i-nʉsi x we-pa

he-lose x he-fight-CP he-blood 2 he-x x

‘he lose x he fought his blood ...’

S .na.nʉ7pin.ko.wik.ki.pa.tʉ.nʉ.?.ja.yaj.wʉ.7i.nʉ7pin.tʉp.ji.7o.wa

na-nʉ7pin ko-wik-pa tʉn x jayaj-wʉ 7i-nʉ7pin tʉp ji 7owa

I-blood other-scatter-IC x deal_with marry-CP he-blood sunset x macaw

‘I scatter blood for others x deal with, married his blood (at) sunset’

(18) .wʉ-tzʉk.ja.naks.tzʉ7.na.nʉ7pin.wʉ.7i.nʉ7pin

wʉ-tzʉk ja naks-tzʉ7 na-nʉ7pin-wʉ 7i-nʉ7pin

array x pound-do I-blood-REL he-blood

‘array x do pounding one of my blood his blood’

(27) .mi.si.ti.7owa.we.pa.na.nʉ7pin.wʉ

misit 7owa wepa na-nʉ7pin-wʉ

x macaw x I-blood-REL

‘... macaw x one of my blood’

(35) .ju7tzi.nʉ7pin.te.ne.?.ji.?.?.si

ju7tzi nʉ7pin tene x ji x x si

and_then blood

‘and then blood ...’

(44) .ju7tzi.na.tokoy.?.7i.ko_pak.7i.?

ju7tzi na-tokoy x 7i-kopak 7i-x

and_then I-lose x he-head he-god

‘and then I destroy the god head’

T tʉp.ji.mi.si.na.wʉ.7i.si.tum_7ame.me.?.matza7_ju7tz.wʉ

tʉp jimisi na wʉ 7isi tum 7ame me x matza7=ju7tz-wʉ

sunset x x x lo one year x title star=pierce-CP

‘at sunset x x lo, one year title star-pierced’

(13) .ki.kajaw.7ips.si.3.?.?

ki kajaw 7ips-si 3 x x

x jaguar 20 and 3 daycount

‘jaguar on the 23rd day’

(19) .13.?.pʉk.kʉ.wʉ.te.ne.na.ka.wʉ

13 x pʉk-kʉ7-wʉ tene naka-wʉ

13 x receive.begin-CP x x-REL

‘on 13 x he began to receive x’

(29) .?.si.ki.wʉ.7i.ku.na.?.?.si.7i.pi.?.tʉ.?.?.ja.wʉ

deal_with

U .x.38.99.38.45.150.170.143.25.149+42.68.63.x.20

.?.7i.?.7i.ko.wik.ki.pa.we.ne.kipsi.ma.?.wʉ

x 7i-x 7i-ko-wik-pa wene kipsi ma x-wʉ

x he-drops he-other-scatter-IC part symbol x

‘x he scatters his liquid for others x’

References

Bett, Steve T. 1996. The Origin of the Alphabet. Unpublished manuscript.

Coe, M. D. 1992. Breaking the Maya Code. New York: Thames and Hudson.

Driver, G. R. 1976. Semitic Writing: From Pictograph to Alphabet. London:

Oxford University Press. (first edition, 1948)

Gaur, A. 1984-7. A History of Writing. London, The British Library.

Gelb, I. J. 1963. A Study of Writing. 2nd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

First published in 1952 by Routledge & Keagan Paul. Ltd. London

Harris, John F. & Stearns, Stephen K. 1997. Understanding Maya Inscriptions: A Hieroglyph

Handbook. Philadelphia: The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and

Anthropology.

Loprieno, Antonio. 1995. Ancient Egyptian: A Linguistic Introduction. Cambridge University Press

Kaufman, Terrence & Justeson, John. 2001. Epi-Olmec Hieroglyphic Writing and Texts. Ms.

Schmandt-Besserat, Denise.1978. The Earliest Precursors to Writing. Sc. Amer. 238:50-59.

Schmandt-Besserat, Denise. 1992. Before Writing. Austin: University of Texas Press.